“…Such a system might work well so long as there was a strong ruler in Kalat, but once his power diminished, the natural result was civil war…”

R. Hughes-Buller, 1901

The tribes inhabiting Baluchistan came under the identical pressures influencing the tribes of Afghanistan during their violent histories. Living at the crossroads of Central Asia had one great disadvantage, and this involved the repeated and serial invasions by migrating tribes pressed from their original homelands and armies bent upon conquest. Generally, these invasions came from the west – along the same route of the tribal migrations. In southern Afghanistan, individual tribes began to organize themselves into larger aggregations in hopes of defending themselves against the repeated threats emerging from the west of their tribal areas. Only the armies of Alexander the Great entered the region using the “northern route,” and even he chose the more obvious southern route as his men struggled to depart from Central Asia. The terrain of the south, less the large desert areas, wasban ideal invasion route and army after army used it.

The Baluch tribes also migrated into the region from the west. Their traditions say they originated from the vicinity of Aleppo, Syria, while scholars studying comparative linguistics suggest their origin in an area of the Caspian Sea, possibly a waypoint with extended residence before being pressed further east by the arrival of more aggressive migrants. Regardless, the Baluch tribes were present in Baluchistan in 1000 A.D. and were mentioned in Firdausi’s book, Shahnamah (the Book of Kings), and like all invading armies they were described as being aggressive, “like battling rams all determined on war.”1

As the last of the migrating tribes to arrive, the Baluch had to displace or assimilate the tribes that were already present and occupying the land. Opposed by the powerful Brahui2 tribes, the Baluch were able to overcome them until an extended civil war broke out between the Rind and Lashari Baluch tribes which weakened them substantially.

After defeating the Brahui under their chief, Mir Chakar of the Rind tribe in approximately 1487, the Baluch kingdom was destroyed in the 30- year civil war between the Rind tribe and its rival, the Lasharis. The Baluch had expanded eastward as they spread into modern Pakistan’s Sind and North-West Frontier Province (NWFP) before being halted by the powerful Mughals of India. The names of Dera Ghazi Khan and Dera Ismail Khan serve as reminders of the Baluch presence in these areas in the 16th century.3

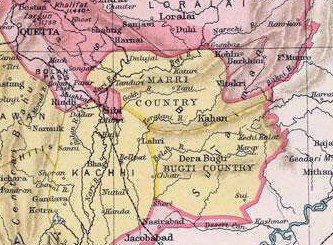

Once they were weakened by civil war, the Baluch tribes fell under the control of the population they once defeated – the Brahui – whose leaders became the powerful Khans of Kalat. Any attempt at understanding of the Baluch tribes requires a careful review of the role played by the Brahui ethnic group. Kalat was well-positioned to divide the two large branches of the Baluch tribes, making them easier to control. To the north of the Brahui and Baluch tribes are broad areas under the control of the Pashtuns – the Kakar, Tarin, Pani, and the Shiranis that occupy Zhob, Quetta-Pishin, Loralai, and Sibi districts as well as the vicinity of Takht-i-Sulaiman.4

The presence of these martial tribes, combined with their allied tribes in Afghanistan, effectively blocked the weakened Baluch tribes from a northward expansion while the Khan of Kalat’s Brahui tribes kept them divided. And the Khans were also limited in options they might consider:

“The rulers of Kalat were never fully independent. There was always … a paramount power to whom they were subject. In the earliest times they were merely petty chiefs; later they bowed to the orders of the Mughal emperors of Delhi and to the rulers of Kandahar, and supplied men-atarms on demand. Most peremptory orders from the Afghan rulers to their vassals of Kalat are still extant, and the predominance of the Sadozais and Barakzais was acknowledged as late as 1838.”5

But the Brahui tribes, speaking Dravidian and not integrated within the Baluch tribes, were able to control the larger and warlike Baluch. More was involved than the Khan’s geographical location. British officer R. Hughes-Buller explained in a section of the 1901 Baluchistan gazetteer: “The Brahuis consist, in fact, of a number of confederated units… of heterogeneous and independent elements possessing common land and uniting from time to time for the purposes of offense or defence, but again disuniting after the necessity for unity has disappeared. “Thus the two bands which unite the confederacy are common land and common good and ill, which is another name for a common blood feud.

“At the head of the confederacy is the Khan, who, until recent times at any rate, appears to have been invested in the minds of the members of the confederacy with certain theocratic attributes, for it was formerly customary for a tribesman on visiting Kalat to make offerings at the Ahmadzai Gate before entering the town. Below the Khan, again, are the leaders of the two the two main divisions, who are the leaders of their particular tribes, and at the head of each tribe as a chief, who has below him his subordinate leaders of clans, sections, etc.

“Such a system might work well so long as there was a strong ruler in Kalat, but once his power diminished, the natural result was civil war…”6

The Brahui not only out-organized the Baluch tribes, they managed to form alliances that further strengthened them. First, they were allied with Persia’s Nadir Shah, then with Ahmad Shah Durrani during the Pashtun invasions of India, before forming an alliance with the British that left the Khans of Kalat in charge of Baluchistan until Pakistan gained its independence in 1947. But once the powerful and influential Khans were removed from their positions from which they controlled Baluchistan, R. Hughes-Buller’s prophecy became self-fulfilling as a series of civil wars and rebellions continued throughout Pakistan’s history.

Hughes-Buller also wrote that “…the welding together of the tribes now composing the Brahui confederacy into a homogeneous whole was a comparatively recent event…. Their traditions tell us that they acquired Kalat from the Baloch, and that they were assisted in doing so by the Raisanis and the Dehwars … the assistance given by the Raisanis is to be noted because the Raisanis are indisputably Afghans.”7

“Welding together tribes” and forming external alliances that allowed the Brahui Khan of Kalat and his forces to maintain significant levels of control over the larger, more populous Baluch and Pashtun tribes found in Baluchistan. Their position, alone, in Kalat allowed the Brahui to split the two large Baluch tribal divisions and this system provided much of the stability that made Baluchistan far more governable than nearby Afghanistan. In 1955, it all changed. Kalat had survived through its alliances, if not its outright subjugation to powerful external forces, such as Nadir Shah’s Persians, Ahmad Shah Durrani’s Pashtuns, and Robert Sandeman’s Imperial British Army, but the newly formed Pakistan was less reliable as an ally. As Pakistan’s ability to control its internal politics, its partially independent “states” were absorbed into Baluchistan to form one of Pakistan’s four provinces in 1955.8

Unfortunately, the “Iron Law of Unintended Consequences” resulted in increasing instability. This was predicted by Hughes- Buller in 1901 in his essay on the Brahui that appeared in the 1901 Baluchistan census: “So long as there was a strong leader in Kalat … once his power was diminished, the natural result was civil war.” More unfortunately, the increasing instability soon started to draw nearby Afghanistan into the political and military fray.

The key question that emerges is simple. If the British realized the importance of the Khans of Kalat in the tribal balance of power that was so critical to Baluchistan’s stability, why did Pakistan’s new rulers miss this? The removal of the stabilizing impact of the Khan of Kalat whose prestige and semi-theocratic influence left a power vacuum in the wake of this unfortunate decision that was soon filled by individual tribal leaders and Hughes-Buller’s “natural result” was not long in coming. Pakistan’s largest political grouping, those speaking Punjabi, were intent upon creating a modern nation-state and Baluchistan had ports and considerable natural resources that were unavailable elsewhere in new Pakistan. Independent states with ports and natural resources were not to be tolerated by the Punjabis.9

When the Brahui Khan of Kalat refused to join the newly created state of Pakistan in 1947, Kalat was swiftly occupied by Pakistan’s army in 1948 – provoking a first rebellion that was led by the Khan’s brother, Prince Karim Khan.10 Unfortunately, nearby Afghanistan was landlocked, lacked the region surrounding Gwadar port, an area ruled by Oman at the time. Equally unfortunate for future Afghanistan-Pakistan relations, Prince Karim Khan and his followers relocated into sanctuaries within Afghanistan’s nearby Kandahar Province. Relations between the ancient state of Afghanistan and the new country of Pakistan had already been poisoned by demands for the creation of Pashtunistan, a vassal state for the Afghans that would have stretched from today’s North-West Frontier Province’s northern limits southward to the Arabian Sea. These conflicting claims developing over Baluchistan resulted in Pakistanis becoming increasingly angry as Afghanistan’s Durrani monarchy began to refer to the region as “South Pashtunistan.” Prince Karim Khan’s arrival in Afghanistan did little to settle the frayed nerves among Pakistan’s new and inexperienced leadership.11

Prince Karim Khan’s short-lived revolt failed because of his inability to attract foreign support for the creation of an independent Baluchistan.

Britain worked to ensure that Pakistan remained stable while the Afghan royal government remained unable to support Karim Khan alone. Stalin’s Soviet Union remained interested, but was non-committal because they felt the greater opportunity for Soviet expansion lay with Pakistan. As a result, Karim Khan was forced to return to Kalat where he continued his rebellion until he and his small group of followers were captured and jailed – by Pakistanis. In the wake of this unsuccessful revolt, relations between Pakistan and Afghanistan became increasingly bitter and as Pakistan’s Punjabis took greater control of Baluchistan’s resources, the Baluch tribes began to build grievances – toward Pakistan. Unfortunately, seeds of a lasting type were being sown in very fertile tribal soil. Now the significantly weakened Brahui tribes were no longer able to act as a buffer between the Baluch tribes while tense relations between old Afghanistan and new Pakistan grew to the point that reconciliation was unlikely to occur. On one side, Afghanistan wanted to see the creation of “Greater Pashtunistan” that would provide both resources and access to ports for the landlocked nation while Pakistan knew the Afghan goal would result in the loss of half of their national territory, leaving its two remaining provinces, Punjab and Sind, unable to survive economically – and militarily. Pakistan had just fought its first war with India and the concept of “Greater Pashtunistan” became a lasting national survival issue for Pakistan.

This situation worsened as Pakistan’s dominant population, the Punjabis, began to complain that Baluchistan comprised 40 percent of Pakistan’s territory, but contained only four percent of its total population. Baluchistan’s tribes failed to recognize the Punjabi logic as a series of rebellions continued, culminating – to date – in a four-year outbreak of fighting in which Pakistan’s new army engaged the Baluch tribes that once fought a 30- year civil war among themselves.

Another careful observer of tribal behavior, British officer C. E. Bruce who spent 35 years in the region following his father’s 35 years, provided useful insights into the relationship between the tribes and the emerging town-based and generally “de-tribalized” inhabitants:

“…the politically minded of the official class, to which must be added the ‘middlemen,’ as well as the ‘intelligentsia,’ were jealous of the tribal leaders. ‘They looked upon them as revolutionaries and against the interests and aspirations of the educated classes.’ For, as Sir Henry Dobbs pointed out, ‘Civil officials are mostly educated Orientals brought up in towns, who have a great dislike and suspicion of the tribes, the tribal organization, and the tribal chiefs, and more often than not are out to destroy them by every means in their power.’ Written of Irak [sic], it was equally true of the frontier.”12

Bruce also wrote about the position of the tribal leaders regarding the growing animosity with the emerging town elites:

“Up to now you have always worked through us. Just because a man can read and write it does not necessarily mean that he is a better man or that he can control our tribes better than we can. Yet these are the men you are putting over our heads and deferring to. And what have been the results?”13

Here lies the clue to understanding the tension between the rural tribes and the urban classes, led by Pakistan’s Punjabis, as they looked at the land and resources under the control of tribal chiefs from the Baluch and Pashtun ethnic groups. The process controlled by the urban elites that began in 1947 is still underway that was described by C. E. Bruce:

“…more often than not are out to destroy them by every means in their power.”

By 1973, Pakistan’s government had run to the limits of their patience with the Baluch tribes. Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto imposed central rule, arrested the principal Baluch leaders, and ordered 70,000 troops into the province. A student of Baluchistan’s politica, Selig Harrison, wrote accurately about this stage of the Baluch rebellion:

“At the height of the fighting in late 1974, American-supplied Iranian combat helicopters, some of them manned by Iranian pilots, joined the Pakistani Air Force in raids on Baluch guerrilla camps. These AH-1J Huey-Cobra helicopters provided the key to victory in a crucial battle at Chamakung in early September when a force of 17,000 guerrillas of the Marri tribe, one of the 27 major Baluch subdivisions, were decimated. “… Allowing for distortion by both sides, nearly 55,000 Baluch were fighting in late 1974, some 11,500 of them in organized, hard core units. At least 3,300 Pakistani military men and 5,300 Baluch guerrillas as well as hundreds of women and children caught in the crossfire, were killed in the four year war…. “Although military conflict between the Baluch and the central government dates from the creation of Pakistan in 1947, the wanton use of superior firepower by the Pakistani and Iranian forces during the 1973-1977 conflict instilled in the Baluch feelings of unprecedented resentment and a widespread hunger for a chance to vindicate their martial honor.”14

By this time, Baluch guerrillas had been allowed to shelter in Afghanistan, once again implicating the Afghan government in the eyes of Pakistan’s leaders. But the impact was greatest on the Baluch tribes, especially the Marri tribe that suffered a military defeat and heavy losses at the hands of the Pakistani and Iranian air forces – that flew American helicopters. For the Baluch tribes, not only was their tribal territory now split and occupied by Pakistan, Iran, and Afghanistan, instead of becoming Greater Baluchistan, their resources were now being appropriated for use in Pakistan’s larger provinces, Sind and Punjab.

One of the Baluch leaders predicted the future from his safe haven in Afghanistan:

“If we can get modern weapons,” said guerrilla leader Mir Hazar at the Kalat-i-Ghilzai base camp in southern Afghanistan, “it will never again be like the last time…. Next time we will choose the time and place, and we will take help where we can get it….”15

Low level insurgent operations continued until 2005 when an event occurred to galvanize the Baluch tribes into action. A female Baluch doctor was raped by four Pakistani soldiers guarding the Sui gas fields at Dera Bugti. Instead of the Marri tribe attacking Pakistani forces, this time it wasthe Baluch Bugti tribe doing the fighting.16 Time magazine provided details:

“In Pakistan’s Baluchistan province, nothing is held in higher regard than a woman’s honor, and the allegations of rape have the rough-and-tumble province, rich with natural gas fields, up in arms literally. Baluch tribesmen have attacked a refinery and pumping station at the Sui gas fields, have sabotaged the pipeline that sends the natural gas to the rest of Pakistan, have blown up railway lines, and have rocketed the provincial capital, Quetta. In response, President Pervez Musharraf has

sent 4,500 paramilitary troops, backed by 20 tanks and nine helicopter gunships, to Baluchistan to try to restore order. It will be a tricky mission. ‘This could be our last battle,’ Baluch tribal chieftain Attaullah Khan Mengal told Time. ‘At the end of it, either their soldiers will be standing alive, or we will.’ “…Workers at PPL reported the incident to Akbar Khan Bugti, the Nawab (or ruler) of the powerful Bugti clan. He says they told him the assailants were four soldiers in the Pakistani army. (Government troops protect the gas facilities.) Says the Nawab: ‘This gang rape took place on our land, in our midst. It has blackened our name.’ “The Nawab says he is taking the woman’s violation personally, and he can muster 4,000 armed men to back him up. Other leaders from the Mengal and Marri tribes have vowed to join him in his campaign for justice.”17

Soon, Akbar Bugti and some Marri leaders were killed in attacks by the Pakistani military. A Pakistani newspaper reported the details, but left out the reason for the revolt, the rape of the Baluch doctor:

“Nawabzada Baramdagh Bugti, grandson of Nawab Bugti, was among the dead but Agha Shahid Bugti said he couldn’t confirm the report. A private TV channel said that Mir Balaach Khan Marri was also killed in the operation. However, the report could not be confirmed. Mr. Durrani also said that Nawab Akbar Bugti had been killed along with two of his grandsons, adds Online.

“According to the sources, security forces started the operation in Bhambhoor area three days ago using heavy weapons and helicopter gunships. On Saturday, the sources said, more troops were inducted into the operation and helicopter gunships shelled the area throughout the day. “The sources said that helicopter gunships targeted the Chalgri area of Bhambhoor mountains and dropped troops who took action in the area. Armed militants of Marri and Bugti tribes resisted the troops and heavy fighting was reported for several hours.”18

And the survivors of the Pakistani raid? As usual, they went across the border into Afghanistan’s sanctuaries in what may be an implicit warning by the Afghan government to the Pakistanis to halt their alleged support for the Taliban insurgency or face a Baluch insurgency quietly supported by Afghanistan. Akbar Bugti’s grandson19 and probable heir, Brahmdakh Bugti, took the usual route into the safety across the border, but this only adds

to the tension between Afghanistan and Pakistan while both the Bugti and Marri tribes took casualties from the Pakistani army attacks. This will ensure a ready supply of antagonized militant tribesmen who will be available to rally to support the first charismatic leader to emerge against the Pakistan government that remained determined “more often than not are out to destroy them by every means in their power,” as C. E. Bruce’s words became prophetic. He knew that the “middlemen” living in towns believed that tribes must be eliminated as social organizations if new nation states are to survive and his prophecy is clearly playing out in Baluchistan.

The dictum “more often than not are out to destroy them by every means in their power” appears to have played itself out as well among the Brahui since they seem to have vanished from the tribal and political scene. The very ethnic group that assembled a powerful confederation to control the Baluch tribes is no longer a major participant and is usually reported as being assimilated into the Baluch tribes. There was no doubt in the reports filed by R. G. Sandeman in 1869:

“…with reference to the present disturbed state of Khelat, and the effect it has on the Khan’s hill subjects, the Murrees, Boogtees, &c…. The whole of Beloochistan, from Humund (a town of Dera Ghazee Khan) to the sea, was under the sway of Nurseer Khan of Khelat, a chief noted for his justice and prowess. He kept the Murrees, Boogtees, and other tribes resident along the Kafila route from Central Asia, as in good order as he did the people of the plains….”20

Another report showed the authority of the Khans of Kelat:

“…Still there is the fact … that the Shum Plain belongs chiefly to the Murrees and Boogtees (nominal subjects of the Khan of Khelat….”21

But all of the tribal balance of power shifted dramatically when the Pakistanis absorbed Kalat. The last Brahui leader, Ahmad Yar Khan, declared Kalat independent in 1947 and Pakistan’s army occupied Kalat and forced the Khan to sign the accession documents.22 Since then, the Brahui influence in Baluchistan has nearly vanished and observers of the slowly evolving insurgency in Baluchistan should remember the following:

“Such a system might work well so long as there was a strong ruler in Kalat, but once his power diminished, the natural result was civil war…”

The Baluch

(Baloch, Balooch, Beluch, Biluch)

Tribal Structure

The Baluch ethnic group is comprised of approximately 15-25 independent units, more akin to confederations than tribes. Baluch tribal hierarchies are somewhat loosely defined, being based more on alliance and location than tribal identity. Largely independent from one another, each tribe recognizes a clear internal hierarchical structure, a characteristic that differentiates the Baluch from the more egalitarian neighboring Pashtun tribes. This hierarchic structure greatly impacts Baluch tribal unity and interaction with other groups. The Baluch have traditionally been more responsive to both internal and external authority and more willing to incorporate outsiders than Pashtun tribes.

The Baluch are broadly divided into eastern and western linguistic groupings with the Brahui ethnic group falling between. The western Baluch tribes, referred to as Mekrani Baluch after the Mekran region, is the smaller of the two and includes those tribes located in Mekran Division, Kharan District of Kalat Division, Chagai District of Quetta Division in Baluchistan, and those living in southeastern Iran and southwestern Afghanistan. Most of the tribes of the eastern grouping, referred to as Sulaimani Baluch after the Sulaiman Range, are located primarily in Sibi Division, Baluchistan.

Others live in Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan, and large numbers live outside Baluchistan in Punjab and Sindh Provinces. A few also live in the North-West Frontier Province. The western or plains Baluch have historically been seen as more peaceful than the eastern or hill Baluch.

The British who dealt with the Baluch from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s saw both the western and eastern Baluch as easier to manage than the Pashtun tribes to the north and northeast. Stereotypes of the independent, egalitarian Pashtun with a strong sense of Pashtun identity contrast with those of the less independent, more hierarchical Baluch who mix more freely with other tribes. The stereotypes still exist, even among the Baluch and

Pashtuns themselves. Pashtun tribes usually claim descent from a common ancestor and recognize a familial-like bond within their division, clan, and tribe. They also recognize a very strict common set of characteristics that make one a Pashtun, including speaking Pashtu and following the Pashtun code or Pashtunwali. The Baluch on the other hand define their tribe according to more political and geographic criteria: loyalty to an authority and common location. Anyone choosing to live under the authority of the tribal chief can be considered a part of the tribe. An outsider wishing to join a Baluch tribe or section first moves into a Baluch tribe’s area, shares in the tribe’s good and ill fortune, is eventually able to obtain tribal land, and is fully admitted upon marrying a woman from the tribe.

The tendency of Baluch tribes to take on outside groups or members, and likewise for groups or members to leave one tribe for another, makes establishing a basis for a tribal hierarchy difficult. One often encounters the same sub-element split between two or more tribes. To further complicate matters, elements sometimes change their names or take on the name of their host, even in the case where they are not ethnically Baluch. In many parts of Baluchistan, it is popular to be considered a Baluch, so non-Baluch will sometimes take on Baluch tribal names, and after many years, may become considered as such. For example, Gichkis, Khetrans, and Nausherwanis are considered to be of non-Baluch origin (Khetrans do not even speak Baluchi), and yet multiple sources list them as Baluch in tribal hierarchies.

The structure within each Baluch tribe follows a more or less common pattern:23

I. Tuman/Toman (Tribe): The Baluch are divided into tumans led by a tumandar/ tomandar (chief).24 The term tuman also refers to a Baluch village.

A. Para/Phara (Clan): Tumans are divided into paras led by a mukadum/ mukadam (headman or chief).

1. Pali/Phalli (Sept or Division): Paras are divided into palis led by a headman, sometimes called a wadera.

a. Family: Palis are sometimes further divided into family groups led by the head of the family, sometimes called a motabar.

A grouping called a sub-tuman occurs in some cases between tuman and para and is a large clan or sub-tribe, having its own significant sections akin to clans. Examples of these are the Haddiani clan of the Leghari tribe, the Durkani and Lashari clans of the Gurchani tribe, the Ghulmani clan of the Buzdar tribe, the Shambani clan of the Bugti tribe, and the Mazarani clan of the Marri tribe.

According to legend, when the Baluch first arrived in Baluchistan, they were united under one headman, one Jalal Khan, but soon split either along ancestral lines or based on which headman they chose to follow as they spread north and east across Baluchistan. Some sources indicate the Baluch are essentially made up of three or five main tribal groupings, though these vary according to the source. Some list the Narui, Rind, and Magzi, some the Rind, Magzi, and Lashari, and some the Rind, Hot, Lashari, Kaheri, and Jatoi.25 In addition to these, there were several other unaffiliated Baluch tribes. These divisions seem to serve little purpose today. Though a Baluch tribe may hearken back to their Rind or Lashari origins, they are independent of these tribes.

Analysis of multiple sources indicates the following are the primary Baluch tribes in Pakistan:26

PAKISTANI BALUCH

Bugti:

Durrag/Nothani/Khalpar/Masori/Mondrani/Notheri/Perozani/Raheja/Shambani.

Bugti (aka Bughti): An eastern Baluch tribe located almost exclusively in Dera Bugti District of Sibi Division, Baluchistan. A few also live in Sibi District of Sibi Division and Barkhan District of Zhob Division. The Bugtis, along with the Marris, Dombkis, and Jakranis, are known as the “hill tribes” and have historically been more independent and warlike than the rest of the Baluch. In the past they raided their neighbors, including those in Sindh and Punjab Provinces, and were the most troublesome Baluch tribes for the British. Today the Marri and Bugti tribes lead the Baluch nationalist movement, along with the Mengal Brahuis. As of 1951, there were approximately 31,000 Bugtis..

Buledi:

Gholo/Hajija/Jafuzai/Kahorkani/Kotachi/Lauli/Pitafi/Raite.

Buledi (aka Boledi, Bolidi, Buledhi, Bulethi, Burdi): Originally located near the coasts of Iran and Pakistan, the Buledi moved north and east into Kalat Division, Baluchistan and northern Sindh, near the Indus River, having been pushed out of Mekran by the Gichki tribe. Some likely remained in Sistan va Baluchestan Province, Iran and Mekran Division, Baluchistan. Most sources list the Buledi as belonging to the eastern Baluch, but some list them as western. One source lists them as a Rind clan. As of 1951, there were approximately 12,500 Buledis.

Buzdar:

Gulman/Namurdi.

Buzdar (aka Bozdar): Located in Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab. The Buzdars are of Rind descent, but have become an independent tribe.

Chandia:

Chandia (aka Chandya): Located primarily between the Indus River in Sindh and the Baluchistan border where they have reportedly assimilated with the local inhabitants. They also reside in Dera Ismail Khan District of the North-West Frontier Province and Muzaffargarh District, Punjab. They may have originally been a Leghari Baluch clan.

Dombki:

Baghdar/Bhand/Brahmani/Dinari/DirKhani/Fattwani/Gabol/Galatta/Galoi/Ghaziari/Gishkaun/ Gurgel/Hara/Jekrani/Jumnani/Khosa/Lashari/Mirozai/Muhammandani/Shabkor/Singiani/Sohriani/Talani/Wazirani.

Dombki (aka Domki, Dumki): An eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in the vicinity of Lahri in Bolan District of Nasirabad Division,Baluchistan, but also found in Sindh. The Dombkis are hill tribes, and like the Marri and Bugti, carried out raids against their neighbors up to the late 1800s. The Dombki, Marri, Bugti, and Jakrani tribes often feuded with and raided one another, but sometimes allied against other tribes or the British. Dombkis are reputedly the storytellers of the Baluch and the recorders of Baluch genealogy. As of 1951, there were approximately 14,000 Dombkis.

Drishak:

Drishak: Located primarily in the vicinity of Asni in Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab. The plains tribes between the eastern border of Baluchistan and the Indus River in Punjab and Sindh, including the Drishaks, Gurchanis, Lunds, and Mazaris, suffered most from the raids conducted by the hill tribes, the Bugtis, Dombkis, Jakranis, and Marris. The plains tribes generally cooperated with the British who controlled Punjab and Sindh

from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s.

Gichki:

Dinarzai/Isazai.

Gichki (aka Ghichki): A western Baluch tribe located primarily in Panjgur District of Mekran Division, Baluchistan. The Gichkis are not ethnically Baluch, likely originating in Sindh or India as Sikhs or Rajputs, but now speak Baluchi and have become assimilated into the Baluch. The Gichki likely also absorbed a number of smaller Baluch tribes in the Mekran region. The Gichki reportedly entered Mekran around the end of the 17th century and, though a small tribe, by inter-marrying and using other tribal militias, soon became a powerful tribe in the area. In the late 1700s, the Brahui Khan of Kalat seized control of the Mekran region, but allowed the Gichki chiefs to manage it as a state within the Khanate. In the late 1800s,

the Nausherwanis, who had entered western Baluchistan from Iran and settled in Kharan District of Kalat Division, expanded into Mekran, reducing Gichki power until the British checked their advances. As of 1951, there were approximately 3,500 Gichkis.

Gurchani:

Chang/Durkani/Holawani/Hotwani/Jikskani/Jogiani/Khalilani/Lashari/Pitafi

/Shaihakani/Suhrani.

Gurchani (aka Garshani, Gorchani, Gurcshani): Located in the vicinity of Lalgarh, near Harrand in Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab. They are reportedly originally descended from the Dodai, a once important tribe that no longer exists. The Gurchani tribe has over time absorbed elements of the Buledi, Lashari, and Rind Baluch. The plains tribes between the eastern border of Baluchistan and the Indus River in Punjab and Sindh, including

the Drishaks, Gurchanis, Lunds, and Mazaris, suffered most from the raids conducted by the hill tribes, the Bugtis, Dombkis, Jakranis, and Marris.

The plains tribes generally cooperated with the British who controlled Punjab and Sindh from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s.

Hot:

Singalu.

Hot (aka Hut): Located primarily in central Mekran Division, Baluchistan, but also found in the vicinity of Bampur in Sistan va Baluchestan, Iran. They are a significant tribe in both areas. According to legend, they are one of the five original Baluch tribes, descended from Jalal Khan, the others being the Jatoi, Kaheri, Lashari, and Rind tribes, though others say they are the aboriginal inhabitants of the Mekran region and are not ethnic Baluch.

Jamali: Babar/Bhandani/Dhoshli/Manjhi/Mundrani/Pawar/Rehanwala/Sahriani/Shahaliani/ Shahalzal/Taharani/Tingiani/Waswani/Zanwrani.

Jamali: An eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in northern Sindh, but also found in Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan, on the border between Baluchistan and Sindh. As of the late 1800s, they were reported to be a small, poor tribe of farmers and herders, numbering about 2,500. As of 1951, there were approximately 15,000 Jamalis.

Jatoi:

Jatoi (aka Jatui): A wide-ranging Baluch tribe located in the following areas: Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan; Dera Ghazi Khan, Lahore and Muzaffargarh Districts, Punjab; Dera Ismail Khan, North-West Frontier Province; and northern Sindh. According to one source, they are no longer a coherent tribe but are spread among other Baluch tribes. According to legend, they are one of the five original Baluch tribes, descended from Jalal Khan, the others being the Hot, Kaheri, Lashari, and Rind tribes.

Kaheri:

Bulani/Moradani/Qalandrani/Tahirani.

Kaheri (aka Kahiri): A small, eastern Baluch tribe located in Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan. According to legend, they are one of the five original Baluch tribes, descended from Jalal Khan, the others being the Hot, Jatoi, Lashari, and Rind tribes.

Kasrani:

Kasrani (aka Kaisrani, Qaisarani, Qaisrani): Located in the Sulaiman Range along the northwestern border of Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab. The most northerly of their clans resides on the border of Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab and Dera Ismail Khan District, North-West Frontier Province. They are reported to be originally descended from the Rind tribe.

Khetran: The Khetran tribe is not Baluch and so is not included in the Baluch tree, but they are closely associated with the Baluch and warrant some mention. Like the Gichki, they are thought to be of Indian origin, but unlike the Gichki who have taken on the Baluchi language, the Khetran speak an Indian dialect akin to Sindhi and Jatki. Some sources class the Khetran among the Baluch hill tribes, as they formerly shared the same propensity for raiding as the Bugtis, Dombkis, Jakranis, and Marris. The Khetrans allied with the Bugtis against the Marris when conflicts arose, though conflicts and alliances among hill tribes were short-lived. As of 1951, there were approximately 19,500 Khetrans.

Khosa:

Balelani/Khilolani/Umrani.

Khosa (aka Kosah): An eastern Baluch tribe located in Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan, Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab, and in the vicinity of Jacobabad in northern Sindh. Some sources list them as a Rind clan, though one source claims they are of Hot descent. As of 1951, there were approximately 11,300 Khosas.

Lashari:

Alkai/Bhangrani/Chuk/Dinari/Goharamani/Gulllanzai/Mianzai/Sumrani/ Muhammadani/SPachi/Tajani/Tawakalani/Tumpani/Wasuwani.

Lashari (aka Chahi, Lashar, Lishari): An eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in Baluchistan, but also found in small numbers in the vicinity of Bampur in Sistan va Baluchestan, Iran. According to legend, they are one of the five original Baluch tribes, descended from Jalal Khan, the others being the Hot, Jatoi, Kaheri, and Rind tribes. The Rinds and Lasharis, originally enemies, allied and conquered the indigenous populations of modern Kalat, Nasirabad, and Sibi Divisions in the 16th century. As of 1951, there were approximately 11,000 Lasharis.

Leghari:

Chandya/Haddiani/Haibatani/Kaloi/Talbur.

Leghari (aka Lagaori, Lagari, Laghari): Located primarily in Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab, but also found in Barkhan District of Zhob Division, Baluchistan and possibly in northern Sindh. According to one source, the Leghari are a Rind Baluch clan.

Lund:

Ahmdani/Khosa/Lund/Rind.

Lund (aka Lundi): Located primarily in Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab. The Lund is a large tribe divided into two sub-tribes, one located at Sori and the other in Tibbi. The Sori Lunds are more numerous than the Tibbi Lunds. The plains tribes between the eastern border of Baluchistan and the Indus River in Punjab and Sindh, including the Drishaks, Gurchanis, Lunds, and Mazaris, suffered most from the raids conducted by the hill tribes, the Bugtis, Dombkis, Jakranis, and Marris. The plains tribes generally cooperated with the British who controlled Punjab and Sindh from the mid-1800s to mid-1900s.

Magzi: Ahmadani/Bhutani/Chandraman/Hasrani/Hisbani/Jaghirani/Jattak/Katyar/Khatohal/ Khosa/Lashari/Marri/Mughemani/Mugheri/Nindani/Nisbani/Rahajs/Rawatani/Sakhani/

Shambhani/Sobhani/Umrani.

Magzi (aka Magasi, Magassi, Maghzi, Magsi): An eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in Jhal Magsi District of Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan. The Magzi were historically farmers but occasionally committed raids against neighbors. They, along with the Rinds, accepted the authority of the Khan of Kalat in the late 1700s. The Magzis and Rinds, who border one another occasionally, feuded in the past. The Magzis, though fewer in number, defeated the Rinds in 1830. As of 1951, there were approximately 17,300 Magzis.

Marri:

Bijarani/Damani/Ghazni/Loharani/Mazarani/Miani.

Marri (aka Mari): An eastern Baluch tribe located almost exclusively in Kohlu District of Sibi Division, Baluchistan; some also reside in northern Kalat and Nasirabad Divisions in the Bolan Pass area. The Marris, along with the Bugtis, Dombkis, and Jakranis are known as the “hill tribes” and have historically been more independent and warlike than the rest of the Baluch. In the past they raided their neighbors, including those in Sindh and Punjab Provinces, and were the most troublesome Baluch tribes according to the British. Today the Marri and Bugti tribes lead the Baluch nationalist movement, along with the Mengal Brahuis. As of 1951, there were approximately 38,700 Marris.

Mazari:

Balachani/Kurd.

Mazari: An eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in the vicinity of Rojhan in southern Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab, and between the Indus River and the border of Sibi Division, Baluchistan in northern Sindh. The plains tribes between the eastern border of Baluchistan and the Indus River in Punjab and Sindh, including the Drishaks, Gurchanis, Lunds, and Mazaris, suffered most from the raids conducted by the hill tribes, Bugtis, Dombkis, Jakranis, and Marris. The plains tribes generally cooperated with the British who controlled Punjab and Sindh from the mid-1800s to mid- 1900s. Prior to British rule, the Mazaris were known as “pirates of the Indus” because of attacks they conducted and fees they extorted from traders on the river. Most recently, following the rape of a female doctor at the Sui gas facility in 2005, the Bugti, Marri, Mazari, and Mengal Brahuis joined forces and attacked the facility, resulting in gas shortages throughout Pakistan.

Nausherwani (aka Naosherwani, Nawshirvani): The Nausherwani tribe is not Baluch and so is not included in the Baluch tree, but they are closely associated with the Baluch and warrant some mention. Their origins are obscure, but they have now fully merged with the Baluch. They primarily inhabit Kharan District of Kalat Division, Baluchistan and Sistan va Baluchestan, Iran. The Nausherwanis, who nominally fell under the authority of the Khan of Kalat, were the most powerful tribe in the Kharan area as of the early 1900s. Around that time the British checked their efforts to expand south into the Mekran region.

Rakhshani:

Rakhshani (aka Bakhshani, Rakshani, Rekhshani): A western Baluch tribe located in Kharan District of Kalat Division and Chagai District of Quetta Division, Baluchistan and along the Helmand River in southern Afghanistan. There are also Rakhshanis in eastern Baluchistan, Sindh, and Iran. Some list the Rakhshani as a Rind Baluch clan and others as a Brahui tribe.27 The Rakhshanis of Kharan were loyal to the Khan of Kalat and well-disposed toward the British as of the early 1900s. As of 1951, there were approximately 35,000 Rakhshanis.

Rind:

Buzdar/Chandia/Gabol/Godri/Gulam/Bolak/Hot/Jamali/Jatoi/Khosa/Kuchik/Kuloi/Lashari/

Leghani/Nakhezal/Nuhani/Raheja/Rakhsani.

Rind: The Rind is a western Baluch tribe. Their headquarters is reportedly in Shoran in Jhal Magsi District of Nasirabad Division, but they are also located in Quetta and Mekran Divisions in Baluchistan, Dera Ghazi Khan, Muzaffargarh, and Multan Districts in Punjab, and Dera Ismail Khan District in North-West Frontier Province. Many other Baluch tribes claim to be Rinds or descended from Rinds. Many of those listed as Rinds are now completely independent and have long-since moved away from the Rind core. This could account for sources reporting such a wide geographic distribution of the tribe. According to legend, the Rind tribe is one of the five original Baluch tribes, descended from Jalal Khan, the others being the Hot, Jatoi, Kaheri, and Lashari tribes. The Rinds and Lasharis, originally enemies, allied and conquered the indigenous populations of modern Kalat, Nasirabad, and Sibi Divisions in the 16th century. They, along with the Magzis, accepted the authority of the Khan of Kalat in the late 1700s. The Magzis and Rinds, who border one another, occasionally feuded in the past. The Magzis, though fewer in number, defeated the Rinds in 1830. As of 1951, there were approximately 26,400 Rinds.

Umrani:

Balachani/Burian/Dilawarzai/Ghanhani/Jonghani/Malghani/Misriani/Nodkani/Paliani/

Sethani/Sobhani/Tangiani.

Umrani: A small eastern Baluch tribe located primarily in Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan. Some may also live between the Indus River and eastern border of Baluchistan in Sindh. As of 1951, there were approximately 2,400 Umranis.

The Baluch in Afghanistan for the most part have different names and groupings from those in Baluchistan and are not usually included in the Baluch tribal lists provided by British sources from the 1800s and 1900s. The only Baluch tribe tha seems to inhabit territory on both sides of the border is the Rakhshani. The Baluch in Afghanistan are mostly nomads living primarily in Nimruz Province, along the banks of the Helmand River and on the western border of Afghanistan between Kala-i-Fath and Chakhansur (Zaranj). Some sources place them all along the southern border of Afghanistan in Nimruz, Helmand, and Kandahar Provinces, with small pockets farther north in Farah, Badghis, and Jowzjan Provinces. The following are the most commonly mentioned Baluch tribes in Afghanistan:28

AFGHAN BALUCH

Gorgeg:

Gorgeg (aka Gargeg, Ghurchij, Gorgaiz, Gorget, Gurgech, Gurgeech, Gurgich): Located in southern Afghanistan along the Helmand River. According to one source, the Gurgech (Gorgeg) are a section of the Rakhshani Baluch.

Kashani:

Kashani: Located in southern Afghanistan along the Helmand River.

Manasani:

Mamasani (aka Muhammad Hasani, Muhumsani): Located in southern Afghanistan along the Helmand River and in Farah Province. There are also some Mamasani located in Mekran Division, Baluchistan, Pakistan, but their relationship to one another is unclear.

Nahrui:

Nahrui: Located in southern Afghanistan.

Rakshani: Gurgech/Jianzai/Sarai/Usbakzai.

Rakhshani (aka Bakhshani, Rakshani, Rekhshani): Located in southern Afghanistan. They are divided into the following sections: Badini, Jamaldini, Gurgeh, Jianzai, Usbakzai, Saruni, Betakzai, Sarai, and Kalagani.

Reki:

Reki (aka Rek, Rigi, Riki): According to legend, the Reki remained behind in Persia (Iran) when the majority of the Baluch tribes moved into Baluchistan. Many still remain in Iran, but according to one source, some live in central Baluchistan, Pakistan, and southern Afghanistan.

Sanjarani:

Sanjarani (aka Sinjarani): Located in southern Afghanistan in Nimruz and Helmand Provinces, along the Helmand Valley. The Sanjarani Baluch claim to have originally come from Baluchistan about 1800. Some are also located in Iran.

The following are Baluch tribes in Sistan va Baluchestan Province, Iran:29

IRANIAN BALUCH

Baranzai:

Baranzai: Located in Sistan va Baluchestan. They may be of Pashtun origin.

Damani: Yarmuhammadzai.

Damani: Located in Sistan va Baluchestan. The Damani are divided into the Gamshadzai and Yarmuhammadzai sections. Some may also be located in Baluchistan, Pakistan.

Garmshadzai: Arzezai/Jehangirzai/Kerramzai/Muhammadzai.

Hot:

Hot: Located in along the coast in Sistan va Baluchestan, Iran and also in Mekran Division, Baluchistan, Pakistan. As of 1923, they were reported to be the largest Baluch tribe living in Iran. Many of them were nomadic.

Ismailzai:

Ismailzai: Located in Sistan va Baluchestan. Most are nomadic. The Reki tribe borders them to the east. They are noted to be stricter in their religious observances than their neighbors.

Kurd:

Kurd (aka Kurt): The Kurds are thought to be identifiable with the Kurds currently located in northwestern Iran, northern Iraq, and southern Turkey. They were reportedly induced (presumably by the Shah of Persia) to settle in Sarhad, Sistan va Baluchestan in order to keep the Baluch in check. However, they got along relatively well with the Baluch and conducted raids against Persian as well as Baluch territory. While acknowledging their Kurdish origins, they now refer to themselves as Baluch.

Lashari:

Lashari: The Lasharis are a well-known Baluch tribe in Baluchistan, Pakistan, but some are nomadic and live in Iran around Bampur in Sistan va Baluchestan, Iran. The relationship between the Lasharis in Iran and Pakistan is unknown.

Nausherwani:

Nausherwani: Though not originally a Baluch tribe, some sources list the Nausherwanis as such or as a Rind Baluch clan. The Nausherwanis listed as Baluch lived in Sistan va Baluchestan as of 2003. They enjoyed close ties to the Nausherwanis in Baluchistan, Pakistan.

Rais:

Rais: Located primarily along the Iranian coast in Sistan va Baluchestan. Some also live in Mekran Division along the Pakistan coast in Baluchistan.

Reki: Natuzai.

Reki (aka Rek, Rigi, Riki): As of the late 1800s, the Reki were said to be numerous and scattered over southern Iran and between Kuh-i-Taftan Mountain and the Helmand River. They were primarily herders. Reki are also located in Afghanistan, but their relationship with the Iranian Reki is unknown.

Taukhi: Gurgich/Jamaizai/Saruni.

Taukhi: Located in Sistan va Baluchestan. Many of the Baluch tribes in Iran hearken back to Taukhi origins. It is unclear if Taukhi is a separate tribe or a hereditary group encompassing several tribes.

Geography

According to tradition and historical evidence, the Baluch entered their present territory from the west—some legends claim from as far west as Syria—arriving in Mekran in approximately the 7th century. From there they spread north into Kalat Division and east into Sindh and Punjab Provinces. They currently inhabit parts of Baluchistan, Sindh, and Punjab Provinces, Pakistan, parts of southeastern Iran, and parts of southern and northwestern Afghanistan. Some also live in the Middle East, and some may live in Turkmenistan and Tajikistan. Pashtun tribes border them on the north and northeast, Punjabis and Sindhis on the east, and Persians on the west. The Brahui ethnic group, residing in Kalat Division, interrupts the Baluch tribal extent within Baluchistan. Most Baluch practice limited nomadism, though some are settled agriculturalists. The Baluch inhabit an area that varies geographically from mountains, to plains, to deserts, and climatically from semi-arid to hyper-arid. As of 1981, approximately half of the Baluch resided in Baluchistan Province. A high percentage resided in Punjab and Sindh Provinces and Sistan va Baluchestan Province, Iran, and fewer lived in Nimruz, Helmand, Badghis, and Jowzjan Provinces, Afghanistan and the North- West Frontier Province, Pakistan. Some have migrated to the Middle East, primarily to Oman, and Baluch speakers can be found in Turkmenistan and Tajikistan. As of the early 1900s, one quarterof the population of Sindh Province was estimated to be Baluch. As of the late 1800s, the Baluch held most of Dera Ghazi Khan District, Punjab Province. However, as of the early 1900s, the Baluch living to the east of the Indus River in Sindh and Punjab no longer spoke the Baluchi language and had more or less assimilated with their neighbors.

Traditionally, many Baluch were nomadic herders who practiced limited agriculture. Though

cultivation has increased with improved irrigation, many Baluch, especially in the Chagai area of Quetta Division, are still nomads. As of the early 1900s, most Baluch in Zhob Division were nomads, though they were beginning to acquire land. Even settled Baluch tend to view themselves as a nomadic people, the term “Baluch” often being used to refer to nomads in general. During times of droughts, normally settled Baluch might migrate to a more prosperous tribal area, where they would receive assistance from fellow tribesmen. Nomadic Baluch live in blanket tents called ghedans/gedans/gidans, made of goat hair and

generally consisting of 11 pieces, about three feet wide by 15-24 feet long. The pieces are stitched together and stretched over curved wooden poles.

Wealthy families use a separate ghedan to shelter their livestock, but most families live with their animals in the same ghedan. A group of ghedans constituted a tuman. Some hill nomads live in small groups in three to four-foot high loose stone enclosures covered by a temporary roof of matting or leaves. The Kachhi Plain in Nasirabad Division is a common winter residence for nomadic Baluch, Brahui, and other tribes.

The Baluch have at one time occupied, and likely continue to occupy, the following areas:

Afghanistan

• Badghis Province:

As of the late 1800s, there were approximately 650 families of Baluch who claimed to have moved there from Baluchistan Province..

• Farah Province:

The Mamasani Baluch resided in Farah Province as of the early 1900s.

• Helmand Province:

Most Baluch live along the Helmand River. – Deshu.

• Jowzjan Province:

A very small number of Baluch lived in Jowzjan Province as of the late 1800s. – Shebergan.

• Kandahar Province

• Nimruz Province:

Most Baluch live along the Helmand River or around Chakhansur (Zaranj) near the Iranian border.

– Chahar Burja

– Chakhansur (Zaranj)

– Rudbar.

Iran

• Sistan va Baluchestan

Oman

Pakistan

• Baluchistan

– Kalat Division:

As of 1951, 79,398 Baluch resided in Kalat Division, in Kalat, Kharan, and Lasbela Districts. A few Baluch also live in Khuzdar and Mastung Districts.

– Mekran Division:

As of 1951, 71,840 Baluch resided in Mekran Division.

– Nasirabad Division:

The Baluch reside in Jhal Magzi District and in southern Bolan District. Some may also live in or migrate to Nasirabad District. They occupy the following villages, among others: Gandava, Bhag, Dadhar, Lahri, Shoran, and Jhal. Some hill Baluch from the east may still winter in the Kachhi Plain in Nasirabad Division.

– Quetta Division:

The Baluch are scattered over the southern portion of Quetta District, Quetta Division. They also reside in Pishin, Killa Abdullah, and Chagai Districts. Many of the Baluch living in Chagai are nomads. As of 1951, 13,233 Baluch resided in Quetta Division.

– Sibi Division:

As of 1951, 110,953 Baluch resided in Sibi Division, most in Kohlu and Dera Bugti Districts.

– Zhob Division:

The Baluch reside in Barkhan and Musa Khel Districts and in the Duki and Sinjawi Sub Divisions of Loralai District.

As of 1951, 25,107 Baluch resided in Zhob Division, most in Loralai District.

• North-West Frontier Province:

Most Baluch in the North-West Frontier Province reside in the vicinity of Dera Ismail Khan.

• Punjab:

The Baluch primarily occupy the area of Dera Ghazi Khan, between Baluchistan (Zhob and Sibi Divisions) and the Indus River. A few Baluch also reside in Multan, Muzaffargarh, and Lahore.

• Sindh:

The Baluch primarily occupy the area between Baluchistan (Sibi and Nasirabad Divisions) and the Indus River.

Tajikistan

Turkmenistan

United Arab Emirates

The following are the significant features and towns found in Baluch areas:

Rivers:

• Helmand River,

Nimruz and Helmand Provinces, Afghanistan.

• Hingol River,

Lasbela District, Kalat Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

• Indus River:

The Baluch live mostly to the west of the Indus River in Punjab and Sindh Provinces, Pakistan.

• Sori River:

There are multiple streams and rivers in Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan named Sori, but the primary is located in Dera Bugti District and flows southeast toward the Indus River.

Valleys:

• Kalat Valley,

Kalat Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan. Baluch, along with Brahuis, Dehwars, and Babi Pashtuns reside in the Kalat Valley.

Mountains:

• Bugti Hills,

Dera Bugti District, Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan. The Bugti tribe resides in the Bugti Hills.

• Central Mekran Range,

Kech District, Mekran Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

• Chagai Hills,

Chagai District, Quetta Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan. Many Baluch living in Chagai are nomads.

• Giandari Range:

The Giandari Range is located on the border of Baluchistan (Dera Bugti District, Sibi Division) and Punjab Provinces, Pakistan. It is part of the end of the Sulaiman Range. The Bugti tribe inhabits the area.

• Kirthar Range,

Sindh Province, Pakistan. The Kirthar Range is located to the east of Khuzdar District of Kalat Division, Baluchistan.

• Marri Hills,

Kohlu District, Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan. The Marri tribe resides in the Marri Hills.

• Mekran Coast Range,

Gwadar District, Mekran Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

• Ras Koh Hills,

Baluchistan Province, Pakistan. The Ras Koh Hills are located on the border between Kharan District of Kalat Division and Chagai District of Quetta Division. The Baluch living in the Ras Koh Hills are principally nomads.

• Sulaiman Range,

Pakistan: The Sulaiman Range runs north and south through Pakistan, roughly parallel to the Indus River, ending in Baluchistan in the Giandari Range and the Marri and Bugti Hills.

Passes:

• Bolan Pass,

Bolan District, Kalat Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: The Bolan Pass has strategic significance as the major communication route between Afghanistan and Punjab and Sindh Provinces, and the coast of Pakistan. It is located at approximately latitude 29 30’ N. and longitude 67 40’ E., about five miles northwest of the town of Dadhar. The pass itself is a succession of narrow valleys between high ranges. The Bolan River runs through it. Some Marri tribesmen live in the area of the Bolan Pass.

Plains:

• Kachhi Plain,

Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Some Baluch inhabit the Kachhi Plain, and some tribes, including the Marri and Bugti Baluch, migrate there in the winter.

Ports:

• Gwadar Port,

Gwadar District, Mekran Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Gwadar Port is located on the Arabian Sea at the entrance to the Persian Gulf. The port is extremely significant strategically and economically, and control of it has caused contention both historically and in the present day. Construction to make Gwadar a functioning deep sea, warm water port began in 2002, and it became fully functional on 21 December 2008. Baluch nationalist groups have opposed the port’s construction, due to concerns the Baluch people will not benefit from its opening. They contend the government of Pakistan will employ the thousands of people required to operate the port from outside Baluchistan, primarily from the Punjab, which will disenfranchise the Baluch residents and also drastically alter the demographics of the area. Many Baluch fishermen have already suffered due to not being able to access their of Oman, who had been forced to flee Oman. Sultan-bin-Ahmed eventually returned to Oman and became Sultan but retained claims on Gwadar, which resulted in a dispute over whether Gwadar had been loaned or permanently gifted to him. Oman eventually sold it back to Pakistan in 1958.

• Ormara,

Gwadar District, Mekran Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Location of Pakistan naval base.

• Pasni,

Gwadar District, Mekran Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Location of Pakistan naval base.

Significant Towns:

• Dadhar,

Bolan District, Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Dadhar is located at the southern entrance of the Bolan Pass.

• Dera Bugti,

Dera Bugti District, Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Dera Bugti is a relatively small town, but serves as the headquarters of the Bugti tribe.

• Gandava,

Jhal Magzi District, Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan

• Jhal,

Jhal Magzi District, Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

• Kahan,

Kohlu District, Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Kahan is a relatively small town, but serves as the headquarters of the Marri tribe.

• Kalat,

Kalat District, Kalat Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: Brahuis are the primary residents of Kalat, but some Baluch reside there as well. Kalat is the headquarters of the Brahui Khan of Kalat.

• Quetta,

Quetta District, Quetta Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan: A mixed population of Baluch, Brahui, and Pashtun tribes reside in Quetta, along with many muhajirs (immigrants who came from India during Partition). Quetta is the headquarters of the Taliban’s senior leadership..

• Shoran,

Bolan District, Nasirabad Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

• Sibi,

Sibi District, Sibi Division, Baluchistan Province, Pakistan.

Military Installations:

Baluchistan nationalist groups are opposed to Pakistan army presence in Baluchistan and contend the Baluch are proportionately under-represented in the Pakistan military in general.

• As of 2006, there were military cantonments in the towns of Quetta, Sibi, Loralai, and Khuzdar.

• As of 2006, three out of Pakistani’s four naval bases were located in Baluchistan at Gwadar, Ormara, and Pasni.

Refugee Camps:

Following the Soviet invasion of Afghanistan in 1979, over three million refugees fled to Pakistan (another 2.9 million entered Iran).

THE BRAHUI (Brahvi)

Ethnology

The Brahuis are the dominant and most numerous race in Baluchistan. British ethnology documents do not fully determine the Brahui origin except to say, they are possibly of the Tartars, while more recent census reports (1998) lend to the possibilities of Turko-Iranian extraction (the same with the Afghan and Baluch).

The name Brahui means “highlander,” as opposed to Narui (Baluch) “lowlander.” They are divided into a number of tribes or khels (kheil) and are a wandering, unsettled nation. The Brahui always reside in one part of the country in summer and in another during the winter; they likewise change their immediate places of residence many times every year in quest of pasturage for their flocks – a practice which is rare among the Baluch

tribes.

The Brahuis are equally faithful in an adherence to their promises, and equally hospitable with the Baluch, and on the whole [as noted by British], are preferred as to their general character.

The 1930 Military report on Baluchistan notes that the “Brahui tribe [is] based on common good and ill; cemented by obligations arising from blood feud. Unsurpassed in strength and hardiness; excellent mountaineers and good marksmen; “mean, parsimonious, avaricious, exceedingly idle…”

Language

The bulk of the present Baluch and Brahui populations are bilingual, and sometimes trilingual. Baluchi and Brahui may be their mother tongues but they are equally fluent in Sindhi and Saraiki.

Religion

Brahuis are all Sunni Muslims and their external forms, such as marriage and interment, are practiced according to the tenets of that sect. They are, however, very lax as to religious observances and ceremonies, and very few of their tomans are furnished with a place of worship.

Location

Occupy the great mountainous band extending from the south of Quetta to Lasbela. In the northeast of Kharan, Brahuis are numerous. Brahui tribes usually migrate to the plains of Bolan District for winter from Kalat, Mastung, and Quetta districts and return to their homes after winter.

TRIBES OF THE BRAHUI

Note: Locational and other relevant information pertaining to Brahui tribes and sub-tribes is available but has not yet been consolidated into product format.

ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF TRIBES

ALPHABETICAL LISTING OF TRIBES

Tribal Element /Ethnic Group/ Tribe/ Division Sub-Division/Section/ Fraction

Ababaki /Brahui/ Mengal (Mingal)/ Shadmanzai/ Pahlwanzai/Ababaki

Adamani /Brahui/ Zahri(Zehri)/Jattak/Adamani

Adamzai/Brahui/Sarparra(Sirperra,/ Sarpara)

Adamzai

Adenazai /Brahui/ Zahri (Zehri)/ Bajoi /Adenazai

Afghanzai /Brahui/ Rekizai /Afghanzai

Ahmadkhanzai/Brahui/Muhammad Shahi/ Samezai (Samakzai)/ Ahmadkhanzai

Ahmadzae (Ahmadzai) /Brahui/Kambarani (Kambrani)

Ahmadzae /(Ahmadzai)

Ahmadzai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Sahtakzai Ahmadzai

Ahmadzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Ahmadzai

Ahmadzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Khidrani Ahmadzai

Ahmedari Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Ahmedari

Aidozai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Aidozai

Aidozai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan) Jahl (lower) Nakib Aidozai

Ajibani Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Ajibani

Ajibari Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Ajibari

Akhtarzai Brahui Raisani Rustamzai Akhtarzai

Akhundani Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Akhundani

Alamkhanzai Brahui Langav Ali Alamkhanzai

Ali Brahui Langav Ali

Alimuradzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Khidrani Alimuradzai

Tribal Element Ethnic Group Tribe Division Sub-Division Section Fraction

Alizai Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/

Deggaun)

Alizai Alizai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Alizai

Allahdadzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Allahdadzai

Allahyarzai Brahui Langav Ali Allahyarzai

Amaduni Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in

Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Tirchi Amaduni

Amirzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Zagar Mengal (of Nushki) Badinzai Amirzai

Anazai Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Tirchi Anazai

Angalzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Angalzai

Azghalzai Brahui Gurgnari Azghalzai

Baddajari Brahui Kalandrani Baddajari

Badduzai Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae)

Badduzai

Badinzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Zagar Mengal (of Nushki) Badinzai

Baduzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Lotiani Baduzai

Baduzi Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Baduzi

Bahadur

Khanzai

Brahui Nichari Bahadur Khanzai

Bahadurzai Brahui Muhammad Shahi Jhikko Bahadurzai

Bahdinzai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Sahtakzai Bahdinzai

Tribal Element Ethnic Group Tribe Division Sub-Division Section Fraction

Bahl (upper)

Nakib

Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan)

Bahl (upper) Nakib

Bahurzai (Bohirzai) Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Bahurzai (Bohirzai)

Bajai (Barjai) Brahui Bajai (Barjai)

Bajezai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Zagar Mengal (of Nushki) Badinzai Bajezai

Bajoi Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Bajoi

Balochzai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Umarani Balochzai

Balokhanzai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Balokhanzai

Bambakzae Brahui Bambakzae

Bambkazai Brahui Muhammad Shahi Bambkazai

Bangulzai Brahui Bangulzai

Bangulzai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Bangulzai

Bangulzai(Bangulzae)

Brahui Bangulzai(Bangulzae)

Bangulzais Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Bangulzais

Banzozai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Jattak Banzozai

Baranzai Brahui Bangulzai(Bangulzae)

Baranzai

Baranzai Brahui Kambrari (Kambari) Baranzai

Baranzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Baranzai

Baranzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Zagar Mengal (of Nushki) Nozai Baranzai

Beguzai Brahui Rekizai Beguzai

Bhadinzai Brahui Kalandrani Ferozshazai Bhadinzai

Bhadinzai Brahui Nichari Bhadinzai

Bhaet Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Bhaet

Bhuka Brahui Bhuka

Bhuldra Brahui Bhuldra

Bijarzai Brahui Kalandrani Halazai (Claim connection to the Kalandrani Brahuis)

Bijarzai

Bijarzai(Bijjarzai)

Brahui Bangulzai(Bangulzae)

Bijarzai (Bijjarzai)

Bijjarzai Brahui MuhammadHasni (Mamasani,Mohammad Hassani)

Bijjarzai

Bizanjau(Bizanjo,Bizanju)

Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo,Bizanju)

Bizanzai Brahui Isazai Bizanzai

Biznari Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Gichkizai Biznari

Bohirzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Bajoi BohirzaiBolan Mengal(Comment:May be just the Mengals located in BolanDistrict)

Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Bolan Mengal (Comment:May be just the Mengalslocated in Bolan District)

Brahimzai Brahui Lahri Brahimzai

Brahimzai Brahui Nichari Brahimzai

Bratizai Brahui Langav Ali Bratizai

Buddazai Brahui Dehwar (Knownin Baluchistan asDehwar, in Iran-Tajak,in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/Deggaun)Pringabadi Buddazai

Burakzai Brahui Kalandrani Burakzai

Burakzai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Sheikh Husaini Burakzai

Burjalizai Brahui Shahbegzai Kambrari BurjalizaiChakarzai Brahui MuhammadHasni (Mamasani,Mohammad Hassani)

Chakarzai Chamakazai Brahui Dehwar (Knownin Baluchistan asDehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, inAfghanistan-Dehgan/Deggaun)Mastungi Chamakazai

Chamrozae

(Chamrozai)Brahui Chamrozae (Chamrozai)

Chanal Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo,Bizanju) Chanal

Chanderwari Brahui Kalandrani Chanderwari

Changozae(Changozai)Brahui Changozae(Changozai)

Charnawani Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Charnawani

Chaunk Brahui Rekizai Chaunk

Chhutta Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Chhutta

Chotwa Brahui Chotwa

Daduzai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Daduzai

Dahmardag Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Dahmardag

Dallujav Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Khidrani Dallujav

Darmanzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Hammalari Darmanzai

Darweshzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Tambrari (Tamarari – also noted as “Tamarari” as a separate clan of Brahuis)

Darweshzai

Darweshzai Brahui Kalandrani Darweshzai

Dastakzai Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Dastakzai

Degiani Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Degiani

Dehwar Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Dehwar

Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-

Dehgan/Deggaun)

Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as

Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun)

Dhahizai Nichari Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae) Badduzai Dhahizai Nichari

Dhajola Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Khidrani Dhajola

Dilsadzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Miraji (Mir Haji) Dilsadzai

Dilshadzai Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Dilshadzai Dinarzai Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae)

Dinarzai

Dinarzai Brahui Rodeni (Rodani) Dinarzai

Dinas Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Musiani Dinas

Dodai Brahui Muhammad Shahi Dodai

Dodaki Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as

Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Dodaki

Dombkis Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Dombkis Dost Muhammadzai

Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Dost Muhammadzai

Dostenzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Zarrakzai Dostenzai

Driszai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Sahtakzai Driszai

Durrakzai (Darakzai) Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani) Durrakzai (Darakzai)

Fakir Muhammadzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Fakir Muhammadzai

Fakirozai Brahui Rekizai Fakirozai

Fakirzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Tambrari (Tamarari – also noted as “Tamarari” as a separate clan of Brahuis)

Fakirzai

Fakirzai Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Fakirzai

Fakirzai Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Fakirzai

Ferozai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Umrani (Umarari / Omarari / Homarari – also noted as

“Umarari” as a separate clan of Brahuis) Ferozai Ferozshazai Brahui Kalandrani Ferozshazai

Gabarari Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Gabarari

Gad Kush Brahui Muhammad Shahi Khedrani Gad Kush

Gador Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Gador

Gahazai Brahui Langav Ali Gahazai

Gaji Khanzai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Gaji Khanzai

Gajizai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)Tambrari (Tamarari – also noted as “Tamarari” as a separate clan of Brahuis)

Gajizai

Garr Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Garr

Garrani Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae)

Garrani

Gazainzai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari,

Shirwani , Sherwani) Umarani Gazainzai

Gazazai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Gazazai

Gazbur Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Gazbur

Gazgi Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Jattak Gazgi

Ghaibizai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Ghaibizai

Ghaibizai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Umrani (Umarari / Omarari / Homarari – also noted as “Umarari” as a separate clan of Brahuis)

Ghaibizai

Ghul Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari,

Shirwani , Sherwani)

Ghul

Ghulamani Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Ghulamani

Ghulamzai Brahui Nichari Ghulamzai

Gichki Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Khidrani Gichki

Gichkis Brahui Gichkis

Gichkizai Brahui Sajdi (Sajiti, Sajadi) Gichkizai

Gichkizai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Khidrani Gichkizai

Goharazai Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Mastungi Goharazai

Gorgejzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Gorgejzai

Gorgezai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Gorgezai

Gowahrizai Brahui Raisani Rustamzai Gowahrizai

Guhramzai (Gwahramzai)

Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae)

Guhramzai (Gwahramzai)

Gujjar Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Gujjar

Gul Muhammadzai Brahui Raisani Rustamzai Gul Muhammadzai

Gungav Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Gungav

Gurgnari Brahui Gurgnari

Gwahramzai Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Gwahramzai

Gwahramzai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Gwahramzai

Gwahramzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan) Jahl (lower) Nakib Gwahramzai

Gwahrani Brahui Muhammad Shahi Gwahrani

Gwahranjau Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Gwahranjau

Gwand Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae) Badduzai Gwand

Gwaramzai Brahui Rekizai Gwaramzai

Gwaranjau Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Bajoi Gwaranjau

Gwaranzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Hammalari Gwaranzai

Habashazai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan) Jahl (lower) Nakib Habashazai

Haidarzai Brahui Lahri Haidarzai

Hajizai Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Hajizai

Hajizai Brahui Muhammad Shahi Samezai (Samakzai) Hajizai

Hajizai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Ramadanzai Hajizai

Halazai (Claim connection to the Kalandrani Brahuis) Brahui Kalandrani Halazai (Claim connection to the Kalandrani Brahuis)

Halid Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Halid

Hammalari Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Hammalari

Haruni Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Haruni

Harunis Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Harunis

Hasanari Brahui Kalandrani Hasanari

Hasilkhanzai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani)

Hasilkhanzai

Hasni Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani)

Hasni

Hirind Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Lotiani Hirind

Horuzai Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Miraji (Mir Haji) Horuzai

Hotmanzai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Hotmanzai

Hotmanzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Hotmanzai

Husain Khanzai Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Tirchi Husain Khanzai

Husaini Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani) Husaini

Idozai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Idozai

Ihtiarzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan) Bahl (upper) Nakib Ihtiarzai

Isai (Isazai, Esazai) Brahui Gichkis Isai (Isazai, Esazai)

Isazai Brahui Isazai

Isazai Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Isazai

Isazai Brahui Sumalari (Sumlari) Isazai

Isazai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Musiani Kubdani Isazai

Isiani Brahui Raisani Isiani

Issufkhanzai Brahui Raisani Rustamzai Issufkhanzai

Jahl (lower)

Nakib Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan)

Jahl (lower) Nakib

Jalambari Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Jalambari

Jallabzai Brahui Kalandrani Jallabzai

Jamalzai Brahui Rodeni (Rodani) Jamalzai

Jamandzai Brahui Langav Ali Jamandzai

Jamot Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Jamot

Jangizai Brahui Rekizai Jangizai

Jararzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo,

Bizanju)

Hammalari Jararzai

Jarzai Brahui Sarparra (Sirperra,

Sarpara)

Jarzai

Jattak Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Jattak

Jaurazai Brahui Langav Jaurazai

Jhalawan

Mengal

Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Jhalawan Mengal

Jhangirani Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Jattak Jhangirani

Jhikko Brahui Muhammad Shahi Jhikko

Jiandari Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Jiandari

Jiandzai Brahui Rodeni (Rodani) Jiandzai

Jogezal Brahui Raisani Rustamzai Jogezal

Jogizai Brahui Pandarani (Pandrani, Pindrani)

Jogizai

Jola Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, inAfghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun) Mastungi Jola Jongozai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani) Jongozai

Kahni Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Lotiani Kahni

Kaisarzai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Umarani Kaisarzai

Kakars (Alien group contained among Ali division) Brahui Langav Ali Kakars (Alien group contained among Ali division)

Kalaghani Brahui Muhammad

Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Kalaghani

Kalandrani Brahui Kalandrani

Kalandranis Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Kalandranis

Kallechev Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Kallechev

Kallozai Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Alizai Kallozai

Kallozai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Nakib (Counted among the Sasoli, but really tenants of the Khan) Bahl (upper) Nakib Kallozai

Kamal Khanzai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju)

Hammalari Kamal Khanzai

Kambarani (Kambrani) Brahui Kambarani (Kambrani) Kambrari

(Kambari) Brahui Kambrari (Kambari)

Kanarzai Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Kanarzai

Karamalizai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Karamalizai

Karamshazai Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Karamshazai

Karelo Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Karelo

Karimdadzai Brahui Kalandrani Halazai (Claim connection to the Kalandrani Brahuis)

Karimdadzai

Karkhizai Brahui Bizanjau (Bizanjo, Bizanju) Hammalari Karkhizai

Kasis (Alien group contained among Ali division) Brahui Langav Ali Kasis (Alien group contained among Ali division)

Kassabzai (Shahozai) Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Musiani Kubdani Kassabzai (Shahozai)

Kawrizai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Zarrakzai Kawrizai

Kechizai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Kechizai

Keharai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Keharai

Kehrai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Kehrai

Khairazai Brahui Rekizai Khairazai

Khakizai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Sahtakzai Khakizai

Khalechani Brahui Lahri Khalechani

Khanis Brahui Kambarani

(Kambrani)

Khanis

Khanzai Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Musiani Khanzai

Kharenazai Brahui Isazai Kharenazai

Khatizai Brahui Langav Shadizai (Shadi) Khatizai

Khedrani Brahui Muhammad Shahi Khedrani

Khidrani Brahui Mengal (Mingal) Khidrani

Khidrani Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Khidrani

Khidri Brahui Gurgnari Khidri

Khidro Brahui Kalandrani Khidro

Khoedadzai Brahui Kurd (Kurda) Madezai Khoedadzai

Khurasani Brahui Langav Khurasani

Khushalzai Brahui Kambrari (Kambari) Khushalzai

Khwajakhel Brahui Dehwar (Known in Baluchistan as Dehwar, in Iran-Tajak, in Bokhara-Sart, in Afghanistan-Dehgan/ Deggaun)

Mastungi Khwajakhel

Khwashdadzai Brahui Nichari Khwashdadzai

Kiazai Brahui Kambrari (Kambari) Kiazai

Kiazai Brahui Muhammad Hasni (Mamasani, Mohammad Hassani)

Kiazai

Kishani Brahui Shahwani (Sherwari, Shirwani , Sherwani) Kishani

Koh Badduzai Brahui Bangulzai (Bangulzae) Badduzai Koh Badduzai

Korak Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Korak

Kori Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Sasoli (Sasuli) Kori

Kotwal Brahui Mirwari (Mirwani) Kotwal

Kubdani Brahui Zahri (Zehri) Musiani Kubdani

Kulloi Brahui Langav Kulloi