By

Muhammad Ijaz Laif

Muhammad Amir Hamza

This paper is an attempt to define ethnic nationalism in Pakistan with reference to Balochistan. The federation is weakened by military regimes that cannot understand the real situation of Baloch nationalism and its deep roots among the people of Balochistan. To explain and analyze the problem, the study has used books, journals, newspapers, government documents and interviews for quantitative/explanatory analysis. To analyse the situation, the philosophy of ethnicity and nationalism and their difference has been discussed. Balochistan has become a gateway to Central Asia, Afghanistan, China, and Europe. It is also approachable to West Asia due to the Gawadar port and some other mega projects. Peace, development, rule of law, and political stability has become of utmost priority to the area of Balochistan and Pakistan. Therefore, it is very important to analyze the present situation of Balochistan which includes the characteristics of Baloch nationalism, its roots, brief history, and ethnic elements of Pakistani nationalism, provincial autonomy and the basic causes of Baloch uprising during Pervez Musharraf regime. The paper analyses the seriousness of Baloch nationalist movement and its future’s consequences and impact on the mega projects in Balochistan.

It is also approachable to West Asia due to the Gawadar port and some other mega projects. Peace, development, rule of law, and political stability has become of utmost priority to the area of Balochistan and Pakistan. Therefore, it is very important to analyze the present situation of Balochistan which includes the characteristics of Baloch nationalism, its roots, brief history, and ethnic elements of Pakistani nationalism, provincial autonomy and the basic causes of Baloch uprising during Pervez Musharraf regime. The paper analyses the seriousness of Baloch nationalist movement and its future’s consequences and impact on the mega projects in Balochistan.

Introduction

Ethnicity refers to rather complex combination of racial, cultural, and historical characteristics by which societies are occasionally divided into separate and probably hostile, political families. In its simplest form the idea is exemplified by racial grouping where skin colour alone is the separating characteristics. Almost anything can be used to set up ethnic divisions, though, after skin colour, the two most common by a long way, are religion and language. According to the Dictionary of Politics, ethnicity raises the whole socio-political question of national identity that is why ethnic politics is at its most virulent and important in third world countries whose geographical definition owes often far more to European empire builders to tend them to any ethnic homogeneity.1

Probably, one needs to distinguish between the politics of ethnicity in advanced societies, where it is some what luxurious, given the overall strength of national identity and the relative importance of other basic political issues related to organizing a productive economy, and the Third World, where ethnic divisions may be absolutely central to the problems of organizing a working political system at all.2

Ethnicity is basic since it provides for a sense of ethnic identity where cultural and linguistic symbols are used for internal cohesion and for differentiation from other groups. It is an alternative form of social organization to class formation. W. J. Foltz has identified four types of characteristics that distinguish different ethnic groups. The first characteristic is biological, where members of a group develop common physical characteristics by drawing upon a ‘particular genetic pool’. More important are the next two distinguishing features, cultural and linguistic, where the ethnic group develops a distinctive value system and language. Finally, the ethnic group may evolve a structural identity by developing a particular type of ‘joint’ relations, differing from the way others organize their ‘social roles’.3

Another Sociologist Paul Brass brings “ethnic groups within three definitional parameters, first, in terms of ‘objective attributes’ – some distinguishing cultural, religious or linguistic feature that separates one group of people from another, second, in terms of ‘subjective feelings’ where a subjective self-consciousness exists. Third, in relation to behaviour – that is, how ethnic groups behave or do not behave, especially in relation to other groups, since cultural and other distinctions really come forth to one group’s interaction with other groups.4

Shireen M. Mazari says in her paper that in most heterogeneous states, ethnic identities and groupings exist within the state and national structures, problems arise when ethnic movements is transformed into nationalist movement. As Tahir Amin points out, ethnic movements seek to gain advantages within an existing state, while nationalist movements seek to establish or maintain their own state.5 There are very few modern states, which are ethnically homogeneous. In his study of nation-building, Walker Connor points out that of a total of 132 states existing in 1972, only 12 (9.1%) could be viewed as ethnically homogeneous, while another 25 (18.9%) states consisted of one main ethnic group, which accounted for more than 90% of the state’s total population. In 31 states (23.5%), however, the single largest ethnic group formed only 50-74% of the population, and in 39 states (29.5%), no one ethnic group accounted for even half of the population of the state.6

With the addition of new states into the system, after the disintegration of the Soviet Union, and in the aftermath of continuing decolonization on the African continent since the seventies, the picture would not have altered in terms of the trend. One of the fallouts of decolonization was the resurgence of ethnicity as a means of identity assertion in the newly-independent states – especially, since in many cases, ethnic groups were split across artificially created borders, without regard to natural, geographic borders and divides, especially in Africa. This also led to ethnicity often having a trans- national framework.7

On the other side nationalism is the political belief that some groups of the people represent a natural community which should live less than one political system while leaving others independent and often has the right to demand an equal standing in the world order with others. Although some times a genuine and widespread belief, especially under conditions of foreign rule, it is equally often a symbolic tool used by political leaders to control their citizen. Nationalism has always been useful to leaders because by stressing national unity harping on threats from those who are clearly foreign or different internal schisms can be prepared over or otherwise unpopular policies can be executed. This statement simplifies, the nationalism contrast with internationalist movements or creeds, and it is a means of stressing on local, at times almost tribal, identities and loyalties.8

Nationalism is a feeling of protection of interests of a nation and national state. It should not be intermixed with ethnicity. Sociologist Hasan Niwaz Gardezi describes that Nationalism was and is a great power which developed nation states in Europe. This gave birth to colonialism, and it resulted in the development of multinational aspects of nationalism and imperialism. Due to colonialism, nationalism developed in the clave countries and they got freedom from the yoke of colonialism. Later on, in the new independent states, under the neo-colonial set up, ruling classes have changed this weapon into ethnicity and used it for their own interests under the philosophy of divide and rule.9

According to the Encyclopedia of Wikipedia, nationalism, in its broadest sense, is a devotion to one’s own nation and its interests over those of all other nations. The term can also refer to a doctrine or political movement that holds that a nation usually defined in terms of ethnicity or culture has the right to constitute an independent or autonomous political community based on a shared history and common destiny. For nationalists, the borders of the state should be congruent with the borders of the nation. Extreme forms of nationalism, such as those propagated by fascist movements in the twentieth century, hold that nationality is the most important aspect of one’s identity and it attempts to define the nation in terms of “race” or genetics.10

Nationalism has had an enormous influence in world’s history. The quest for national hegemony has inspired millennia of imperialism and colonialism, while struggles for national liberation have resulted in many revolutions. In modern times, the nation state has become the dominant form of societal organization. Historians have used the term nationalism to refer to this historical transition and to the emergence and predominance of nationalist ideology.11

But ethnic nationalism is more than nationalism. It defines the nation in terms of ethnicity that always includes some element of descent from previous generations i.e. gynophobia. It also includes ideas of a culture shared between members of the group and with their ancestors, and usually a shared language. Membership in the nation is hereditary. The state derives political legitimacy from its status as homeland of the ethnic group, and from its function to protect the national group and facilitate its cultural and social life, as a group. Ethnic nationalism is now the dominant form, and is often simply referred to as “nationalism”.12 Theorist Anthony Smith uses the term ‘ethnic nationalism’ for non-Western concepts of nationalism, as opposed to Western views of a nation defined by its geographical territory. (The term “ethno-nationalism” is generally used only with reference to nationalists who espoused an explicit ideology along these lines; “ethnic nationalism” is the more generic term, and they used it for nationalists who hold these beliefs in an informal, instinctive, or unsystematic way).13

After the collapse of Soviet Union and with the end of cold war, the nation state is being challenged by the drive of racial, cultural and religious minorities for the rights of self-determination. The world is facing a wave of ethno-nationalism. The problem is being faced by both old and new nations, from Great Britain, Russian Federation, Afghanistan, Sri Lanka and Pakistan etc. The myth of national integration or unification is being exploited by the social diversity of constituent minorities.

Pakistan is trying its utmost for the fulfillment of minority’s demand for self-determination. It was an ethno-nationalist state in the post colonial era. Being an independent state, Pakistan largely ignored the social diversity and economic disparities of its people. The construction of national ideology based on pure mechanical national unity and simplistic ideas of cultural homogeneity. The ruling classes of Pakistan neglected the social diversity and ignored the interests of ethnic and regional minorities. This gave the ultimate death blow to Pakistan. A majority of its people broke away to form a separate country Bangladesh. The remainder of Pakistan is under the siege of political instability, ethnic and sectarian conflicts, religious terrorism and economic inequality.14

In Pakistan, the ethnic movements have been of differing varieties, and have shifted from seeking advantage within the state to moving beyond into the realm of ethno-nationalism,15 rather than reverting to the former position. While these shifts have been correlated primarily to internal political developments (for example, in the case of the ‘Sindhu Desh’ movement), in some cases, external developments have had a major influence also (as in the case of the ‘Greater Balochistan’ and ‘Pushtunistan’ movements). The 2002 elections showed a trend that had begun in the last elections (February 1997), that ethnic parties have lost ground to national political parties.16

The roots of these problems lie in Pakistan’s failure to acknowledge and accommodate its ethnic diversity, economic disparities and provisional autonomy. Ethnicity particularly has been much talked about, with little understanding. Pakistan is a multi-lingual, multi-cultural and multi-ethnic society. The constitution of Pakistan provides equal rights and opportunity to all nationalities and ethnic groups in all walks of life. Language and culture of all identities should be promoted and there should be mutual respect and tolerance. Suppression of diversity in the name of Islam, national unity or strong centre is not only violation of basic human and democratic rights but is counter productive to the aims of suppression. Unity among all nationalities, ethnic or racial groups must be sought and can be found within the cultural and ethnic diversity of Pakistan.

Objectives of Study:

This research is about the ethnic nationalism with reference to Baloch nationalism and its political impact in Pakistan. The purpose of the study is to test a hypothesis that the ethnicity, ethnic nationalism is a serious threat to Pakistani federation. The un-democratic forces cannot understand the real situation of provincial autonomy and the power of nationalism. In this respect, the study will endeavor to deal with the following:

1. To discuss the elements of Ethnic Problems in Pakistan.

2. To analyze the historical and political causes of Baloch Insurgency.

3. To evaluate the role of tribal chiefs in the movement.

4. To analyze critically the causes of Baloch insurgency during Musharraf Regime and its threat for the.

5. To discuss the nature of Baloch unrest and its impact on future of Pak-Iran-India Gas Pipeline and other development projects.

At the end recommendations and conclusion will be drawn. The focus of this study is on the Balochistan’s insurgency in 1999- 2007 and state ‘suppression’ by Musharraf regime due to which many workers of Baloch political parties including Akbar Bugti were removed from the scene for ever. It would attempt to examine the impact of these savior state ‘oppressions’ and its consequences on Pakistani politics. The future of federal structure and over all country’s political situation is discussed in this paper.

Methodology

The research problem in this paper is to explain the ethnic and national problems of Pakistan with reference to Balochistan. The existing material on ethnicity, nationalism and provincial autonomy in Pakistan is mostly descriptive and theoretically ambiguous. Thus, the study used secondary sources i.e., books, journals, and newspapers, at times quantitatively to explain and analyze politics and nationalism in Pakistan. In addition, primary sources such as reports are used for quantitative analysis. The study relied on quantitative facts in the data collected because it would help to test hypothesis. The questionnaire that was built for this purpose shall analyze the problem with the help of theoretical framework.

Finally, the study has mainly focused on Pakistan’s provincial problems, general politics and Baloch nationalism. It has excluded otherwise very useful narration of political developments such as a detailed description of the causes of Pakistan’s partition in 1971 and various military actions in Balochistan. It has been done knowingly because it is very difficult to include all in this short paper. The study is intended to explain the problem that has not been dealt with the way the present study does. Therefore, unnecessary details are avoided to fully concentrate on the problem.

Literature Review

Sixty years of Balochi nationalism in Pakistan have had very few impacts in the print media due to the military factor prevailing in Pakistan that has suppressed Balochi nationalism. In order to test the hypothesis, several books on the subject and some original reports and documents of the government of Pakistan are used as a primary source. Various books e.g. Ethnicity and politics in Pakistan by Dr. Feroze Ahmad (1991) Sang-e-Meel Publications, Lahore were relied upon in terms of quantitative/qualitative facts to explain the Ethnicity and nationalism in Pakistan.

In addition, reference has been made of another book Adeel Khan (2005) Politics of Identity: Ethnic Nationalism and the State in Pakistan, SAGE publications Delhi, to explain the role of Army, Civil Bureaucracy, political parties and tribal ‘sardars’ in the structure of Pakistani federation. Both the books also cover general politics of Pakistan and Balochistan and the philosophical aspects of ethnicity and nationalism. On the issue of national question of Pakistan and ethnicity, a valuable book was Hasan Niwaz Gardezi’s Understanding Pakistan- the Colonial Factor in Social development, (1991) Maktba Fikro Danish, Lahore. In this book he discusses Balochistan’s tribal belts and its pre capitalist modes of production. About Ethnic and nationality question, he describes the early eruption of ethnic resistance against the central authority in Balochistan.

A valuable historical work of Justice Mir Khuda Buksh Marri Searchlights on Balochi’s and Balochistan (1974), Royal Book Company, Karachi, was also consulted. In In his book, Justice Murri attempted to trace the origin, customs, language and history of Baloch people from Tell-Harire and Allepo in Nothern Syria to ancient Babylonian, Kerman, Balochistan and Delhi from the earliest times to the present. Two important books on national crisis, national integrity and political situation of Pakistan are also consulted for this paper. From Crisis to Crisis by Herbert Feldman (1972), Oxford University Press, Karachi is a valuable writing to examine the administration of the country by Ayub Khan through the instrumentality of the constitution promulgated by him and brought in to effect on the abrogation of martial Law on June 1962.

The second one is Rounaq Jahan’s Book, Pakistan- Failure in National Integration (1972), Colombia University Press,London. In this book, she focused on national development, national integration of Pakistan since 1971. Some valuables articles of Dr. Mubarik, Ishfaq Saleem Mirza, Dr. Anees Alam, and Tahir Muhammad Khan on nationalism, nationality, and the evaluation of Baloch-Pashtoon movement in Balochistan and their contradictions were also consulted, published in Journal of ‘History’ (2005), Fiction House, Lahore.

To explain the historical aspects of the Baloch nationalism, the study relies upon secondary sources like journals, newspapers, magazines and internet resources. The secondary sources helped a lot in terms of explaining the historical background of Baloch nationalism, mega projects in Balochistan, real causes of the unrest in Balochistan. Some primary material in terms of Pakistan Census Report (1998) to quantitatively explain the impact of inters province migration towards Sindh and Balochistan were also accessed.

Interviews of some of the leaders of political parties of Balochistan, intellectuals, experts on Baloch issue were conducted in order to get some information and insight on the Baloch nationalist movement and politics and economic ventures to explain research problem. However, unfortunately, the accessibility to some of the concerned persons was made difficult due to their engagements and critical situation of Balochistan and the judicial crisis of the Supreme Court of Pakistan. The time constraint too proved a setback in this respect. To solve this problem, Chairman of a political party Khaliq Baloch and Rashid Rehman an expert on Balochistan were accessed. This source has been used quantitatively to explain the real situation of Balochistan.

Elements of Ethnic Problems in Pakistan:

Much has been said and written about the history, facts and legitimacy of ethnic problems, grievances and national question of Pakistan. Here, we will only highlight some basic elements of the ethnicity in Pakistan.

Provincial Autonomy:

Provincial rights, regional autonomy, and self-determination are basic types in which the ruling class of the dominated nationality or ethnic group has raised grievances against the domination of the ruling elite of the Punjab. In different part of the country, political elements from time to time raise their voice for complete independence, confederation with only residual powers for the centre, more autonomy within federation, creation of new provinces for different ethnic entities and demand for change in provincial boundaries to create more homogeneous provinces.17

Allocation of Resources:

This is the most important area in which oppressed nationalities and ethnic groups are very sensitive. The resources for which they struggle are financial resources for development and recurrent expenditures, more share in irrigation water, Government jobs, opportunities for professional and higher education and allotment of agricultural land to civil and military bureaucracy in Sindh and Balochistan.18

Inter-Province Migration:

There is a great resentment on migration from Punjab and NWFP to Sindh and Balochistan. Refugees from other South Asian countries, Afghanistan, and Arab countries are also a problem for Balochistan. In 1998, the last Population Census calculated a net migration to a total population ratio of 9.6 for Sindh.19 This migration created a huge burden on limited resources of these provinces. In Balochistan the case of Gawader and the making of cantonments become a sensitive issue, because it will change the demographic balance of Balochistan.

Language and Culture:

This is another sensitive area. Demand for the protection and promotion of languages and cultures of different ethnic groups against the domination of Urdu and neglect of regional cultural heritage. It is a permanent feature in the struggle of different ethnic groups for their identity assertion. In spite of a dominated nationality, Punjabis are deprived of their mother tongue. Language and cultural identity serve as instruments to forging group cohesion and legitimating group demands.20

The major issue, for the leadership, was to frame a viable political system in the aftermath of the state’s creation in August 1947. The preparation of the various drafts for a viable constitution which could satisfy the expectations of all the provinces of the new country reflected the economic, social, political and cultural problems which confronted Pakistan. The failure of the political leadership to accommodate ethnic diversities within a representative political framework was responsible not only for the failure of civilian rule and the military takeover in 1958, but also for the creation of ethno-nationalism.

Nationalism is a product of concept of a nation. Pakistani state has four nationalities in its federation. The ruling class of Pakistan is ignoring this fact since its creation and trying to change its multi-nation status into a single nation. Anees Alam says that in the newly independent states, the institution of state was born and developed under the shadow of colonialism. Now this institution (state) has become involved in ‘negative’ practice to develop a single nation country Pakistan. Creation of Bangladesh and continuous unrest in Balochistan is the result of this state ‘mentality’.21

Political Background of Baloch Insurgency

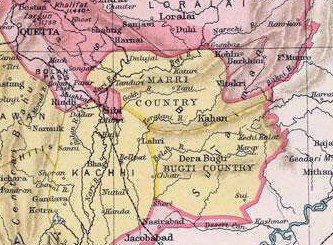

To understand the present insurgency in Balochistan, it is necessary to overview the historical background of the movement. In 1947, there were three independent rulers in independent Balochistan, Khan of Kalat in Baloch areas, Nawab Jogezai in some Pashtoon areas and some other Pashtoon areas were independent. Geographically, Balochistan was distributed into four states or regions. They were (1) Bela (2) Kallat (3) Makran (4) Kharan. The four states were under the Khan of Kallat before the arrival of Britishers. Two agreements were signed in 1878 and in 1939 among Khan of Kalat and the British government.22

The Britisher got Quetta, Noshki, Bolan and Naseerabad on rent from Khan of Kalat. The area of railway line from Jakababad to Taftan was also on rent. In 1947; The Khan of Kalat and other Baloch sardars wanted to be an independent Balochistan. For this purpose they formed Kalat National Party. The forceful merger of Balochistan into Pakistan was the first contradiction of Baloch with Pakistani ruling class.23 When the nominal rulers of Balochistan, the Khan of Kalat, dragged his feet in the early 1950s over signing the Balochistan accession document to Pakistan, the impatient federal government threw diplomacy and negotiation overboard and hastily sent a couple of PAF jets to strafe his palace and make him change his mind.

Natural Gas was discovered in Sui around 1952. Since then, Pakistan has benefited enormously from this cheap source of energy. Balochistan, however, neither had gas for its own use nor was paid royalties which was its due right till the mid-1980s, when General Zia-ul- Haq was trying to mollify the Baloch nationalists since he had his hands full with Zulfikar Ali Bhutto’s People’s Party. Even today, only gas pipeline in Balochistan runs through Quetta, with a proposed pipeline to Khuzdar, still to become a reality. The lack of alternative fuel has denuded; whatever little forest covered the arid province. Only under international environmentalists’ pressure, has the federal government lately conceded to the need for gas supply to Ziarat to save the unique Juniper forest from extinction. The royalties being paid to Balochistan for its gas are lower than those being paid for later discoveries in Sindh and Punjab. This was cause of much heartburning for the Baloch.24

When One Unit was declared in 1955, Sher Mohammad Marri, a tribal ‘wadera’, protested the usurpation of ‘provincial rights’, fled to the hills with a band of loyal tribesmen and started taking pot-shots at the ‘occupying Punjabi army’ The seeds of Baloch provincial awakening gave rise to Baloch nationalism in the aftermath of national elections, the eruption of Bengali separatism and the creation of Bangladesh in 1971. Mr. Bhutto’s PPP won Sindh and Punjab and Sheikh Mujibur Rehman’s Awami League swept East Pakistan, the fact also was that the National Awami Party led by “nationalists” Ghaus Bux Bizenjo, Ataullah Mengal, Khair Bux Marri, Akbar Bugti and Khan Wali Khan dominated Balochistan and the NWFP. At the time, even the Jamiat i Ulema i Islam of Maulana Mufti Mahmud (father of Maulana Fazlur Rehman) thought fit to join hands with the nationalists to espouse the provincial cause.

The 1970s revolt of the Baloch, which manifested itself in the form of an armed struggle against the Pakistan army in Balochistan, was provoked by federal impatience, high handedness and undemocratic constitutional deviation. It was the effect of unjust federal policies and not the cause of them. At that time, Nawab Akbar Bugti served as an agent of the federal government when he was appointed governor of Balochistan by Mr. Bhutto throughout the time of the insurgency and spoke not a word in favour of Baloch rights or provincial autonomy. The greater irony was that the insurgency came to an end following the army coup of General Zia ul Haq against the civilian government of Mr Bhutto.

Soon thereafter, Gen Zia unfolded plans to desensitize the alienated Baloch and Pashtun leadership by a multi-faceted strategy aimed at co-opting the leaders into office while providing jobs and funds in the federal government to the alienated and insecure tribal middle classes. More significantly, he created maximum political space for the religious parties in the NWFP and Balochistan so that they could be galvanized in the jihad against the USSR in neighbouring Afghanistan. The years of Zia’s political machinations had had their effect, and although the PPP emerged as the single largest party in the 1988 elections, it failed to gain an overall majority in the national legislature. Benazir Bhutto’s Prime Ministership was, therefore, the result of a compromise with the existing structures of power, with the division of powers tilted heavily in favour of the President.

In the course of the four elections held in Pakistan since 1988, political coalitions have been built across ethnic lines and the national parties have made inroads into the provinces. (See Appendix I) For instance, after the 1997 elections, the Pakistan Muslim League (PML) chose to form a coalition government with a number of ethnic parties – although it could have ‘gone it alone’. Instead, it formed the coalition with the Awami National Party (ANP), the Balochistan National Party (BNP), Jamhoori Watan Party, The Baloch leaders, who had taken up arms against the Z. A. Bhutto regime, were also brought back into the mainstream after the death of General Zia. While the Baloch political parties remain fragmented, the mainstream national parties increased their support in the Province. The old alignment between the Balochs and Pushtuns also ended as a result of the influx of Afghan refugees into Balochistan.

Although conflicts continued with the centre over the distribution of resources, including water, these issues are not framed in ethno-national terms anymore. The civilian Governments headed by Benazir Bhutto and Nawaz Sharif made overtures to the Baloch nationalists and managed to persuade them to give up violence, despite continuing differences between Islamabad and the Baloch nationalists over questions such as genuine political autonomy for Balochistan, larger allocation of central tax revenue and development funds for Balochistan and payment of inadequate royalty for the gas found in Balochistan and taken to Punjab to sustain its economy.

The return of the Army to power under the President General Pervez Musharraf on October 12, 1999, led to a gradual deterioration of the situation in the province. Amongst the reasons for this were: the traditional grievances of the Balochs over the lack of political autonomy, inadequate royalty payment for gas and lack of economic development. The construction of the Gawadar port by the Army with Chinese assistance without the involvement of the Baloch people and their Government in Quetta in the decision-making related to the port; the award of all major contracts relating to the construction of the port to companies based in Karachi and Lahore; and the re-settlement of a large number of ex-servicemen from Punjab and other parts of Pakistan in the Gawadar and the surrounding areas on the Mekran coast in order to assure the security of the new port. The fact that Pakistan’s nuclear-testing site was located at Chagai in Balochistan also aggravated the grievances due to fears of long-term environmental and health damage.

Analysis of Baloch Ethnic Nationalism during Musharraf Regime

The present phase of Baloch struggle for ‘independence’ was propelled by socio-economic reasons. Baloch-Pakistan relationship did not rest on even keel even after Sui gas started flowing to Pakistani homes and industries in Punjab and Sind, Port Qasim and Gawadar were being developed with Kuwaiti and Chinese assistance. New industrial infrastructures attracted professional and labour forces from Punjab, Sind and other areas of Pakistan.

President Musharraf’s arrival did not improve the situation. Baloch demand for political autonomy, royalty from Sui gas, and award of major work orders to Punjabis and Sindhis and induction of more Frontier Guards and regular army contingents increased the ambience of tension. Islamabad added to the tense situation by rehabilitating large number of ex-servicemen on de-notified tribal land and inducting more NWFP Pushtoons to Quetta areas. Some minor Sardar’s were either bought off or disinherited by affluent Punjabis and rich ex-army personnel. Islamabad even failed to negotiate an acceptable formula on gas, copper, silver, gold and coal royalty. The Baloch Sardars resented the fact that Islamabad had not considered it necessary to consult the provincial government before conducting nuclear tests at Chagai Hills.25

After the military coup in 1999, however, the fight against a ‘common enemy’ once again acquired more urgency than group interests. The military regime’s desperate move to manage Pakistan’s dwindling economy, for which it seemed to believe that the exploration of Balochistan oil and gas resources hold some hope, once again radicalized the nationalists in Balochistan. The military ruler, General Pervez Musharraf announced in December 1999 that exploration work would soon be started.26 Since then nationalist elements have started using harsh language against the federal government. “The army is very strong, but this time it will not get a walkover,” Mengal has been quoted as saying, implicitly pointing to the 1973 military operation launched against trouble-making Baloch tribal chieftains during the tenure of Zulfikar Ali Bhutto government that broke their back.

Since long, a predominant majority of the Baloch nationalist leaders have been agitating against the establishment of proposed army cantonments and the mega projects, including the Gawadar deep-sea port, in Balochistan. “In the name of gigantic projects is a plan under way to settle the Punjabis in Balochistan,” Mengal says.27 Since 2000 the Kachhi Canal, Mirani Dam, Gawadar Port, Makran Coastal Highway, Saindak Copper Project and Quetta Water Supply Scheme were announced by Islamabad. Over 300 percent increase was made in the national budget for development programs in Balochistan. These things have failed to materialize from paper into concrete.

Along with the development programmes came in the Punjabis, Pushtuns, Sindhis and Chinese work forces. The Baloch people suffering from economic distress developed clash of economic interests with the Chinese and other Pakistanis. Examination of economic indices of this period brings out the facts of glaring disparity between Balochistan and Punjab and Sind. The Balochs, like the Bengalis were treated as raw material suppliers.28 The government accuses the nationalist Sardars of being opposed to the mega-projects in particular, and to development in the province in general, for fear that their traditional hold on their areas may be weakened by modernization. However, enlightened nationalists, including the three main nationalist Sardars, Marri, Bugti and Mengal, assert that they do not oppose development, but deprivation of Baloch people’s rights in the name of development and modernization.

Given this background, it is easy to understand nationalist misgivings about further exploration for gas and oil in the province. The tribes have been resisting exploration activities without a fair share in gas and oil development. Whatever little exploration activity has occurred in the past has been either under the protection of military deployments or under agreements with local chieftains. In the case of the latter, the exploration companies have been accused by local people of bad faith and reneging on promises of providing jobs, schools, healthcare and other social infrastructure to the local populace.

The Sandak copper and precious minerals project was supposed to train and employ local youth. Instead, after many false starts and remaining in limbo for almost a decade because of the unwillingness of the federal authorities to provide a paltry Rs 1.5 billion29 as working capital, the project has been revived under Chinese management. The latter, which put up the project in the first place, never forgot its export and earnings potential, and have a contract to run it in return for 50 percent of the profits.30 Out of the remaining, 48 per cent goes to the federal government and Balochistan receives 2 per cent.31 It is also argued that there are no local youths trained or employed in the project, another broken promise in a long line of similar disappointments.

Gawadar port’s strategic and economic value has never been in doubt. In fact it was the Baloch nationalists, at that time in coalition with Nawaz Sharif, who invited the former prime minister to announce the initiation of the project at a rally in Gawadar. But subsequent developments have left these very nationalists bitter. The master plan for the Gawadar port, city and military base adjoining it have never been seen by either the chief minister of the province or been laid for discussion in the Balochistan Assembly.

Along with other development work on the ground, perceptions have developed that the new Gawadar city has turned out to be a major land grab for investors from outside the province, as advertisements in the national and even international media show. Initially, the federal authorities envisaged 2.5 million people being inducted from outside the province. This has now climbed to 5 million. Given that the population of the entire province is only 6-7 million32, the people of Balochistan have raised protest that this massive influx will swamp them; deprive them of a share in the opportunities created by these mega-projects, and wipe out their identity.

The government believes that these are the work of elements opposed to the exploration. One of the radical nationalist, Khair Bux Muree, who had played an active role in the 1970s insurgency, but has been living a secluded life for last two decades, seems to have been chosen for the role of one social element and the government has implicated him in the judge’s murder and put him behind the bar.33

The clash in Balochistan is between ‘aggressive’ modernization (backed by military force) and the Baloch people’s demands for their rights. Force has not yielded good results in the past. It is unlikely to do so in future. The government therefore would be better advised to seek a consensual mode of implementation of the mega-projects the poor people of Balochistan desperately need to overcome decades of neglect and deprivation of rights by bringing the nationalists on board through a fair distribution of the benefits of development and modernization.

Since several years, there was a tension in Sui between the Bugti tribes led by Nawab Akbar Bugti and the federal government over issues of employment, job security, compensation, etc., relating to work conditions in the gas generating and distribution companies that pump sui gas to the rest of the country. But that was presumed to be a local affair. The federal governments of Benazir Bhutto, Nawaz Sharif and General Pervez Musharraf were convinced that Nawab Bugti was extorting money from Islamabad ostensibly on behalf of the Bugti tribesmen who work the gas plants but actually for himself by nudging his fiercely loyal Bugti tribesmen to rocket the pipelines whenever the negotiations get bogged down against his liking.34

Divided, fatigued and shorn of ideological moorings or avowed enemies like Z.A. Bhutto, the Baloch movement melted into memory over the next two decades. Nawab Akbar Bugti was consigned to negotiating rights and concessions only for his Bugti tribesmen in Sui. And the various civilian federal governments that came and went were content to accede to his local pecuniary demands. In the event, what has changed under General Pervez Musharraf to compel the Bugti and Marri tribes to join hands? What has transpired since 1999 to lead to a reinvention of the “Baloch middle class nationalist struggle for provincial rights”?

The military cantonments planned at Gwadar, Dera Bugti and Kohlu are viewed as outposts of repression and control, not development. The Frontier Corps is thoroughly hated and despised as a federal instrument of oppression. With the religious parties rampaging in much of Balochistan and defying the writ of the government, the rise of incipient armed nationalism poses a grave challenge to the stability and security.

In this political seesaw, Mr Bugti was not flexible about terms like ‘gas royalties’, ‘provincial autonomy’, ‘constitutional rights’ etc while portraying himself as the great and patriotic Baloch nationalist fighting for the rights of his province rather than for his tribe. The federal government, on the other hand, seemed falsely obsessed about “the need to open up Balochistan for economic development” and was constantly carping about the exploitative Sardari system in the province that kept the tribesmen in chains and acted as a brake on progress, unfortunately for the stability and security of Pakistan, the truth is different on both counts. There is an unfortunate situation in which a Baloch Liberation Army comprising a few armed bands under tribal and middle class command is conducting military operations against the army in Balochistan. Gawadar is an obvious target as it is perceived as a federal project without provincial approval or participation in which the non-Baloch civil-military elites are ‘grabbing land for a song’.35

The single most critical macro factor was the social and electoral engineering initiated by the military regime in its last five years. By sidelining the mainstream PPP and PML-N parties and their natural progressive allies like the ANP, BNP and others in favour of the religious parties, like Jama’at i Islami and Jamiat i Ulema i Islam, General Musharraf alienated the old non-religious tribal leadership as well as the new secular urban middle classes of Balochistan who see no economic or political space for themselves in the new ‘military-mullah’ dispensation.

Similarly, by undermining the cause of provincial autonomy at the altar of local and federal government, the military regime has threatened the very roots of the constitutional consensus of 1973 enshrined in the Baloch consciousness. If the federal government had also delivered the great development paradigm and provided jobs and office, it might have avoided this sense of deprivation and resentment among the political and economic have-nots of the province. But it hasn’t, Balochistan remains a backwater province, infested by Taliban-type mullahs and opportunist politicians, all beholden to the (military) regime in Islamabad.

The Baloch nationalism, with very few exceptions, tends to be articulated by the local elite and intelligentsia. Why should it be surprising then that some Sardars are voicing the demands of Baloch nationalism? Given the tribal structure of Baloch society the only surprise is that ‘more of them are not doing so’. The Balochistan crisis is becoming worse and more serious. The Balochistan Liberation Army (BLA), after retreating in the face of regular troop’s deployment in Sui, has shown its capability to strike not only all over Balochistan, but even in the heart of the state, i.e. Punjab. In separate incidents gas line to Lahore was blown up near Changa Manga, as was the gas line near Taunsa. Meanwhile rocket attacks and the blowing up of railway lines have preceded apace. Every new day brings news of fresh disasters.36

The intelligence agencies, civil and military, have been bending their backs to convince the government that the ubiquitous foreign hand has been responsible for all the trouble in Balochistan. The finger of accusation has been pointed by these agencies at Iran. The Iranian government has denied more than one time meddling in Balochistan, pointing out that only if peace prevails in Pakistani Balochistan will peace reign in Iranian Balochistan. The logic of this position is that Iran has nothing to gain and the prospect of trouble with its own Baloch nationalist’s resurgent demands for autonomy and rights if it were to ever contemplate support to Baloch nationalists in Pakistan. Much is being made by the government and its hangers-on of the alleged blockage of modernization and development by the Sardars of the Baloch tribes in order not to lose their grip on their subjects. In fact, if it is not the foreign hand, then the Sardars are the authors of all the trouble, according to this official view. This is misplaced propaganda capable of taking in only the uninformed.37

History teaches that nationalism, with very few exceptions tend to be articulated by the local elite and intelligentsia. Why should it be surprising then that some Sardars are voicing the demands of Baloch nationalism? Given the tribal structure of Baloch society the only surprise is that most of them are not doing so. The overwhelming majority of Sardars is, as usual, aligned with the status quo, including leaning on the Centre of their political existence, perks and privileges. The small intelligentsia on the other hand is in the Baloch nationalist camps. Quite progressive people too have been taken in by the government’s propaganda about the Sardars being the sole obstacle to progress and development in Balochistan, in a faint echo of the 1970s, when Zulfikar Ali Bhutto managed to convince the rest of the country, especially the Left, aided considerably by a total news blackout on events in Balochistan, that Balochistan’s resistance to his military operation was only for the defence of Sardari privilege.

People have to understand that a tribal society is at a different stage of historical development. When deprived of its rights for long and oppressed in myriad ways, it resists, its language is inevitably that of nationalism, and its articulation inevitably by the local elite and intelligentsia. Balochistan is no exception. The tilting against Sardars is a red herring that obscures the real issues concerning Balochistan historical grievances becoming inextricably intertwined with the affront to the tribal code of honour in the shape of the rape of a doctor on Balochistan soil and the attempts to protect the perpetrators, especially the principal accused hiding behind his sullied uniform.

Post Bugti Scenario:

Some sources allege that the fourth phase of Baloch insurgency was triggered off by sexual assault on a female doctor, Dr. Shazia Khalid, by a gang of Punjabi employees of the PPL at Sui. Islamabad handled the matter in a cavalier fashion. Accumulated anger incensed the people and they mounted attack on the Sui facility. Nawab Akbar Bugti, the leader of Jamhoori Watan Party of Balochistan, stated that the attack was a manifestation of anger of the people and had nothing to do with nationalist struggle for freedom by the tribes. General Musharraf retaliated by ordering the ISI and the Army to mount operations against rebel Baloch forces headed by Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti. Bugti’s critics alleged that he had rebelled demanding higher royalty payment for Sui gas. These charges have not been proved.38

In his death and the manner in which it was carried out, Sardar Akbar Bugti was likely to become a martyred hero for Baloch nationalism. Bugti, the Sardar or chief of more than 200,000 Bugti tribesmen, was killed along with more than 35 of his followers when the Pakistan Air Force bombed his hideout in the Bhambhore mountain range in the Marri tribal area.39 Pakistani officials declared that at least 16 soldiers including four officers were killed after they went in to mop up the remnants of the Baloch guerrilla group. A fierce battle ensued which led to their deaths. Bugti, a 79-year-old invalid who could not walk due to arthritis, is reported to be buried in the rubble of the cave where he was hiding.40

For months, Pakistani politicians including members of the ruling party had been insisting that the military regime agree to hold talks with the Baloch leaders in order to stop what was becoming an ever-widening civil war in the province. Several security agencies and advisers to President Pervez Musharraf, including the Inter services Intelligence (ISI) and Intelligence Bureau, asked Musharraf to hold talk with the Baloch leaders.

However, other councillors and the Military Intelligence advised him to crush the Baloch leaders, which included three prominent Sardars, Bugti, Khair Bux Marri and Ataullah Mengal. Senior politicians say that Mr. Musharraf’s lack of understanding about the Baloch issue, his underestimation of the growing sense of alienation in all the smaller provinces and the attack on his ego when his helicopter was fired upon by Baloch rebels in 2006, all contributed to his helping him take the decision to kill Bugti.

Bugti was not the leader of the mysterious Balochistan Liberation Army which has been banned by Pakistan, but he was certainly its most visible spokesman over the past three years, as the Baloch insurgency against Islamabad has grown. The army has attempted to divide the Baloch by promising large aid grants to those tribal leaders who support the government, even as Islamabad claims that it is eliminating the Sardari system. Pervez Musharraf may have underestimated Baloch nationalism. Baloch nationalists have long argued that while Islamabad exploits their massive gas and mineral deposits, they give little in return to the province.

In 2006, the ruling Pakistan Muslim League agreed on a package of incentives for the Baloch that included a constitutional amendment giving greater autonomy to the province, but it was overruled by Mr Musharraf and the army who then vowed to militarily crush the rebellion. The army argues that millions have been spent in development, but projects such as the building of the Gawadar port, the building of cantonments and even new roads do not necessarily benefit ordinary Baloch. The projects are defined by the army and its national security needs, rather than through consultations with the Baloch or even the Balochistan provincial assembly. Then the projects are carried out by outside companies who give menial jobs to the Baloch.

By killing Bugti, the president earned the enmity of not just the Baloch rebels but the wider Baloch population who may not believe in taking up arms, but are still frustrated with Islamabad for its failure to develop the province. He might have seriously underestimated the power of Baloch nationalism which has led to four wars with the Pakistan army in the past. Nationalism within the smaller provinces has always been the biggest threat to military regimes just as it was to Mr. Musharraf.

The hanging of former Prime Minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto in 1979, who was a Sindhi, by an earlier military ruler has made Sindhis resentful of the army, while they have, by and large, always voted for the opposition Pakistan People’s Party. In the North West Frontier Province where Talibanization is rampant, Pashtun nationalism is presently taking the form of political Islam.41

By killing Bugti, the army was sending a clear message to nationalists in other provinces as to how they will be dealt with if they rear their heads. However, the smaller provinces are seething with resentment against continued military rule. Their sense of frustration and alienation is growing as they see the army representing only its own interests or that of Punjab, the largest province in the country.

The army is also sending a powerful signal to neighbouring India and Afghanistan. The army has accused India of financing and arming the Baloch rebels, while it has accused Afghan President Hamid Karzai of allowing the Baloch to train in Afghanistan. India and Afghanistan have denied these charges at the highest level, but Pakistani officials say that there is little doubt that the Indians were involved in funding the Baloch movement because of their long-standing involvement with the Baloch and the evidence that arrested Baloch rebels have provided the Pakistani intelligence services.

There is an ever-deepening political crisis in Pakistan which the death of Bugti will only exacerbate. Many people say that the country is rapidly unravelling with Mr Musharraf refusing to give clear-cut guarantees about free and fair elections in 2007, while he insists on running again for another five-year term as president even as he remains army chief. Bugti’s death will only add to the growing fears about the country’s future and the danger inherent in a policy of killing political opponents rather than holding a dialogue with them.

Implications for Pak-Iran-India Gas Pipeline and other Mega Projects

The political unrest in Balochistan and the murder of Akbar Bugti is a serious threat for gas pipeline of Iran, Pakistan and India’s project. During the visit of Iran’s oil Minister Bijan Namdar Zanganeh of New Delhi to discuss the future of the pipeline, anti- government element in Balochistan blew up two gas pipelines sending a message to all parties involved in this pipeline of peace project.42 The area of the Balochistan-Punjab border where the pipeline is supposed to run is one of Pakistan’s poorest areas and its most restive province. In recent years it has been a battleground of private militias belonging to Baloch tribes. Sporadic armed clashes resulted in attacks against water pipelines, power transmission lines and gas installations. Yet, the region is strategically important due to its large reserves of oil and gas. Over the years Islamabad has failed to provide a fair share of the oil and gas wealth in shape of royalty to Balochistan. Lack of economic progress and a deep sense of disaffection have contributed to the distrust between the federal government and the Baloch people.

As a result, the tribes now oppose any energy projects in their area. Since 2003, sabotage of a gas pipeline from Sui to cut off supply to the Punjab has become a routine. Later on, a wave of attacks against gas installations caused the government to send troops to protect the installations. During the era of Mushraf regime and especially in the following year the confrontation is growing more and more. To calm the area Islamabad added carrots to its policy of sticks by increasing investment in regional development projects. However, it seems that violence has resurfaced and the region is sliding into a near war situation.

After the murdered of Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti, it is very difficult for Mushraff Government to snub the Baloch nationalism and insurgency in Balochistan. The attacks of the Baloch Liberation Front and Balochistan Liberation Army fired rockets at the pipeline and exchanged gunfire with the security forces for several hours on government installation.43 During the fire exchange the pipeline caught fire, disrupting supply to a power plant. As we have seen in other parts of the world where pipelines are under attack, ending the onslaught may well prove to be mission impossible. Nevertheless Islamabad has already indicated that the pipeline project will be pursued even were India to decide not to join.44

Human Rights Violations:

There are serious violations of human rights in Balochistan. Thousands of Baloch militants had been killed in the last three decades movement. According to the Carnegie report, in the last 30 years the conflict in Balochistan resulted in 8,000 deaths, 3,000 of them from the army.45 The HRCP report said that up to 85 percent of the 22,000-26,000 inhabitants of Dera Bugti had fled their homes after paramilitary forces shelling repeatedly hit the town. There were alarming accounts of summary executions, some allegedly carried out by paramilitary forces. The HRCP received credible evidence that showed such killings had taken place, across Balochistan, the HRCP team found widespread instances of disappearance of torture inflicted on people held in custody, and on those fleeing from their houses. Carlotta Gall, The New York Times correspondent visiting the area in April 2006 reported having witnessed deep bomb craters caused by MK-82 bombs. According to her, “Hundreds of political party members, students, doctors and tribal leaders have been detained by government security forces, many disappearing for months, even years, without trials in well-documented cases. Some have been tortured or have died in custody.”46

She proceeds to comment, “In places like Dera Bugti and Kohlu, government forces have carried out reprisals against villagers, Baloch leaders and human rights officials say. In a case documented by the Human Rights Commission, the Frontier Corps killed 12 men from Pattar Nala on Jan 11, 2006, after a mine explosion near the village killed some of its soldiers. Two old men from the village who went to the base to collect the bodies were also killed. The next day, the 14 bodies were handed over to the women of the village. Local fighters say the Frontier Corps has carried out 42 such reprisal killings in the last three months of 2006.”47

The first reports about major displacement due to fighting appeared in April 2005 when some 300 government troops were surrounded by thousands of tribal militants in the town of Dera Bugti, located close to Pakistan’s largest gas reserves. The fighting was reported to have displaced around 6,000 people and killed scores of civilians.48 Militants have continued to target gas pipelines, railway lines and electricity networks, and have launched rocket attacks on government buildings and army bases, followed by retaliation and search operations by the military. The security situation for the civilian population has severely worsened due to the use of landmines in parts of the Dera Bugti and Kohlu districts both by rebel forces, in particular the Balochistan Liberation Army, and by the Pakistani army. As of April 2006, more than 50 civilians had been killed by landmine explosions since the beginning of the year.49 The army has used heavy artillery and launched air strikes against insurgent bases; this has also killed and maimed civilians. By December 2005, about 90 per cent of the population in the town of Dera Bugti was reported to have fled and displacement was also reported in the district of Kohlu. During subsequent fighting, thousands of civilians were reported to have fled several areas in the neighbouring Jaffarabad and Sibi districts.50 The situation deteriorated further in the wake of the killing of Baloch tribal leader Nawab Akbar Khan Bugti in August 2006 which was followed by bloody riots. Several have warned that the conflict will go on escalating if the government continues its harsh military response against political opposition groups in the region.

There are no official or UN estimates of the extent of the displacement due to the fighting. One regional human rights organisation says 200,000 people were displaced as of July 2006. The displaced had at that point fled to relief camps or towns in safe areas of Jaffarabad, and the Nasirabad, Quetta and Khuzdar districts of Balochistan, as well as to the Sindh and Punjab provinces. No other source has verified this figure. Another media report says 50,000 remained displaced due to military operations as of July 2006.51

Several reports have testified to the critical living conditions for the displaced that moved to relief camps as well as a general apathy demonstrated by the Pakistani authorities’ vis-à-vis the displaced civilian population. Although the media have not been allowed to move freely in the areas most affected by the violence, deplorable conditions and lack of assistance to the displaced in relief camps have been reported since the onset of the conflict. In May 2006, assistance had not yet reached the camps. The displaced were reported to be living in the open in baking hot weather without food and other facilities. Provincial opposition leaders appealed to international and national humanitarian organisations for assistance.52 The displaced were still reported to be living in temporary settlements without provision for water, sanitation, food, schooling and health care. The government is accused of deliberately blocking access to the displaced populations and has stopped efforts to provide health services in the camps. Official sources said that the displaced were well off and not in need of assistance.53

Conclusion:

Pakistan is a federation of four provinces. Its creation is very unique in nature. The role of provincial units, nationalities and ethnic groups in the creation of Pakistan is basic and fundamental. The pre-partition strategy of the Muslim League was to struggle for provincial autonomy and lose centre for the rights of the Muslims. But after partition all the political parties, army, and civil bureaucracy had become the champion of strong centre. The attitude of strong centre and the refusal of provincial autonomy has played vital role in the creation of Bangladesh in 1971.Again, the ruling class of Pakistan, Civil and military bureaucracy is refusing the rights of self-determination of oppressed nationalities like Balochistan. The guarantee of provincial autonomy that is given in the constitution of 1973 of Pakistan is also denying these reserved rights. The various causes of unrest in Balochistan are serious and that should be addressed and touched by the democratic government in post Mushraf scenario.

Formation of the democratic government in Pakistan and Balochistan provided the opportunity that democratic government should meet with the provincial award among the provinces, royalty of the provincial resources, Gawader port problem, and cantonment issue. The national, regional and international political scenario is very dangerous and complex. Therefore, the Balochistan issue should be addressed as early as possible to strengthen the Pakistani federation.

The new Zardari government should focus on development plans and it must be directed towards the full empowerment of local people. The people must be recognized as stake-holders in the decision-making process, and their interests must be placed at the top of the list of priorities. For this to happen, the people must be given a voice, this is possible only if civil society organizations make greater efforts to visit the areas of deprivation and interact with the people and are allowed to do so. At the same time, all movements must alter their approach to seeking rights from one of aggression, to a broader based initiative aimed at building countrywide and even international alliances for their campaigns.

All steps are taken by the government as well as tribal leaders to end the practice of penal sanctions through jirgas as well as to do away with any form of private prisons that may exist. To meet the needs of people, educational institutions and vocational training centres must be established across Balochistan. Development cannot be limited only to building infrastructure or setting up giant projects. Development plans must focus on building civil society, including establishing press clubs, bar associations and community radio and television networks. This would connect the population of Balochistan to the rest of the country and enhance the cultural environment within which hey lead their lives. The low visibility, negligible educational attainments and virtual lack of any voice in decision making of Balochistani women is a serious hurdle in the development of the province. This situation needs the serious attention of the government, leaders of tribes, regional political parties as well as nationalist movements. In the explosive situation in Balochistan, the more vulnerable members of society, such as children, members of minority communities and unemployed youth not only deserve special protection, their social and economic advancement must be guaranteed through appropriate plans of action. Therefore, it is necessary to treat them very carefully on Issue of Balochistan. The national interests demand that patience, negotiation and compromise should be the hallmark of federal policy rather than knee-jerk army operations and detentions. At the same time, the federal government should make serious efforts to clinch the new development conditions of resource sharing with local tribes and regions. The future of the oil and gas pipelines that are being planned across the mountains and deserts and coasts of Balochistan for the prosperity and stability of Pakistan hinges on a sensible and exclusionary approach rebel killing raises stakes in Pakistan.

It should be remembered that danger in Balochistan is two-fold. The nascent but alienated middle class in the few towns of Balochistan is now rallying behind the nationalists and accepts the sardars spearheading PONM as genuine leaders. At the same time, the developmental lag in the province is sufficient to substantiate the anti-centre stance of PONM. That is why any military action in the province will completely lack local support. The other destabilizing factor relates to the ongoing battle against the Taliban-Al Qaeda combine. The Pashtuns in Balochistan also have serious problems with the federal government’s policy on the Pak-Afghan frontier. This could be troublesome since Pashtun nationalism has also been responsible for the internationally reported presence of the Taliban in the province.

Notes and References

1 David Rober (1987), The Penguin Dictionary of Politics, Penguin Books, New York, pp.111-112.

2 ibid.

3 W. J. Foltz, (1974) ‘Ethnicity, Status & Conflict’ in Bell & Freeman (eds.) Ethnicity and Nation-Building: Interpretational and Comparative Perspectives, Beverly Hills, Calif: Sage Publications, p. 8.

4 Paul R. Brass, (1991) Ethnicity and Nationalism, Sage Publications, Delhi, pp. 18-19.

5 Shireen M. Mazari, Director General of the Institute of Strategic Studies, Islamabad, in her paper presented at the Conference on ‘South and South East Asia in Perspective – 20th and 21st Centuries’, held at the Institute of Political and Social Studies, Lisbon, Portugal, on November 12-14, 2002. Tahir Amin, Ethno-Nationalist Movements of Pakistan (1993), IPS, Islamabad, p. 2.

6 W. Connor, (1972), ‘Nation-Building of Nation Destroying’ in World Politics quoted by Shireen M. Mazari.

7 Shireen M. Mazari,op.cit.

8 David Rober (1987), The Penguin Dictionary of Politics, Penguin Books, New York, pp.111-112.

9 Hassan N. Gardazi (1991) Understanding Pakistan, ‘The Colonial factor in Societal Development,Maktaba Fikro Danish, Lahore, p.49.

10 http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/nationalism accessed on 19-06-2007.

11 ibid.

12 ibid.

13 ibid.

14 Feroz Ahmad (1998) Ethnicity and Politics in Pakistan, Oxford University Press, Karachi, p.15.

15 For example, ‘Greater Balochistan’ movement in the seventies which has dissipated over a period of time, as have the ‘Sindhu Desh’ and ‘Pukhtunistan’ movements.

16 Shireen M. Mazari, op.cit.

17 Feroz Ahmad (1998) Ethnicity and Politics in Pakistan, Oxford University Press, Karachi, p.15.

18 ibid, p.16.

19 Government of Pakistan, Statistics Division Population Census Organization (2001), Census report of Sindh province, Islamabad, p.19.

20 Feroz Ahmad (1998), Ethnicity and Politics in Pakistan, Oxford University Press, Karachi, p.16.

21 Anees Nagi (2005), ‘Nationalism in new independent countries’, History,(special number on nationalism)a biannually Journal,no.24. Fiction House, Lahore, p.55.

22 Adnan Adal (2006), “Historical background of Baloch National Movement”, Monthly Nawa-e-Insan, vol: 6, issue: 11, January 2006.

23 ibid.

24 Zafarallah Jamali’s conversation with newsmen, reported in Dawn, Karachi, August 2006.

25http://www.balochwarna.org/modules/mastop_publish /?tac=Balochistan-Cruches_Of_History accessed on July 13, 2007.

26 http:www.cmkp.tk , accessed on 04-06-2007.

27 Interview with Atta Ullah Mengal by Najam Sethi, Friday Times, Lahore, Febrary, 2006.

28 http://www.balochwarna.org/modules/ mastop_publish/?tac=Balochistan-Cruches_Of_History accessed on July 13, 2007.

29 Interview with Rashid Rehman, currently a freelance contributor, has held editorial positions in various Pakistani newspapers, on January, 2007-06-06.Quoted by http://www.cmkp.tk , accessed on 04-06-2007.

30 ibid.

31 ibid.

32 http://cmkp.tk , accessed on 04-06-2007.

33 ibid.

34 Haroon Rashid’s report in Monthly Herald, Karachi, November-December, 2000.

35 Adeel Khan (2005), Politics of Identity: Ethnic Nationalism and the State in Pakistan, SAGE publications Delhi, p.119.

36 http://www.balochwarna.org/modules/mastop publish/?tac=Balochistan-Cruches_Of_History accessed on July 13, 2007.

37 ibid.

38 ibid.

39 Wajahat Masooad, The murdered of Akbar Bugti (2006) Monthly Nawa-e-Insan.vol.7, September, 2006.LRL No. 279, p. 22.

40 ibid.

41 Dawn, August, 17, 2006, Karachi.

42 http://www.idsa-india.org/an-jul9-9.html accessed on 29-05-2007.

43 Wajahat Masooad, The murdered of Akbar Bugti (2006) Monthly Nawa-e-Insan.vol.7, September, 2006.LRL No.279, p. 22.

44 Dawn, August, 17, 2006, Karachi.

45 http://www.balochwarna.org/modules/mastop publish/?tac=Balochistan-Cruches_Of_History accessed on July 13, 2007.

46 ibid.

47 ibid.

48 http://www.internal-displacement.org/ 6CEF209F30020F37C1257203004E6189/$file/Pakistan accessed on July 13, 2007.

49 ibid.

50 ibid.

51 Dawn,13 July 2006

52 Dawn, 16 April 2006.

53 Dawn, 13 July 2006.

_________________

Courtesy

Pakistan Vision Vol 10 No 1

This paper, therefore, presents a historical survey of the involvement of Balochistan in the power politics of various empirebuilders. In particular, those circumstances and factors have been examined that brought the British to Balochistan. The First Afghan War was fought apparently to send a message to Moscow that the British would not tolerate any Russian advances towards their Indian empire. To what extent the Russian threat, or for that matter, the earlier French threat under Napoleon, were real or imagined, is also covered in this paper.

This paper, therefore, presents a historical survey of the involvement of Balochistan in the power politics of various empirebuilders. In particular, those circumstances and factors have been examined that brought the British to Balochistan. The First Afghan War was fought apparently to send a message to Moscow that the British would not tolerate any Russian advances towards their Indian empire. To what extent the Russian threat, or for that matter, the earlier French threat under Napoleon, were real or imagined, is also covered in this paper.

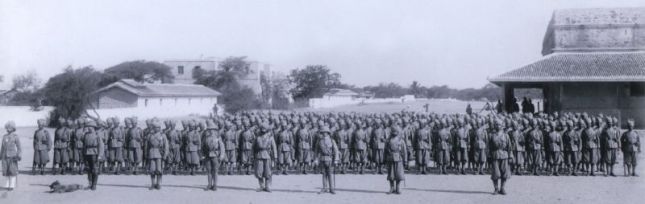

On 7th February Lieutenant Bovet’s men used their gun-cotton to demolish forts at Gushtang, Kaor-i-Kalat and Kala-i-Nao, the adjacent villages having already been burnt by the infantry on 2nd February. Visits were made to the other valleys of the hostile sardars and a flying column under Major G.E. Even was sent north to the higher Bolida valley where the forts at Chib and Koshk were demolished, whilst the Bet fort was occupied. Major Even then seized Kalatak fort and released Diwan Udho Das.

On 7th February Lieutenant Bovet’s men used their gun-cotton to demolish forts at Gushtang, Kaor-i-Kalat and Kala-i-Nao, the adjacent villages having already been burnt by the infantry on 2nd February. Visits were made to the other valleys of the hostile sardars and a flying column under Major G.E. Even was sent north to the higher Bolida valley where the forts at Chib and Koshk were demolished, whilst the Bet fort was occupied. Major Even then seized Kalatak fort and released Diwan Udho Das.

You must be logged in to post a comment.