By: Dr. Simone Tarsitani

Introduction to zikri rituals

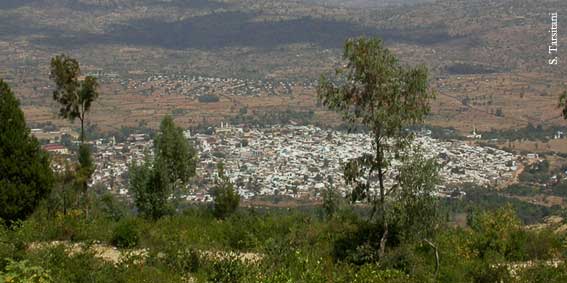

Zikri is the Harari word for the Arabic “dhikr” and refers to an exercise (typical of Sufism), which consists of the repetition of the name of God in order to receive his blessing. The rituals performed in the city of Harar, important centre of Islamic learning in Ethiopia, are derived from the influence of Sufi orders, widespread in the Islamized areas of the Horn of Africa. However, the cult of saints in Harar developed particular beliefs and rules that go beyond the discipline of Sufi orders and zikri rituals can be considered an original expression and one of the unique elements of the culture of this town. The wide repertoire of texts written in the local language, the sung melodies and their rhythmic accompaniment, the ritual and social function of their performance developed distinctive characteristics. Historically and contemporaneously, zikri rituals have permeated Harari life and the repertoire of songs has expanded beyond its origin of liturgical hymns, to become one of the facets of Harari identity.

Zikri is a devotional activity characterized by hymns praising Allah, the Prophet and the Saints. The singing usually follows a responsorial structure lead by a shaykh and accompanied by drums (karabu) and wooden sticks (kabal). The term zikri in Harar means not only the chanting and its ritual context, but also the single devotional song performed in the zikri ritual. What is commonly referred to as ‘zikri ritual’ can comprise slightly different kinds of practices. The most common features consist in the reading of suras from the Quran, recital of prayers, singing of zikri songs, prolonged consumption of khat leaves, tea and coffee, all concluded by a shared blessed meal. Great importance in Harar is given to the Mawlūd, a sacred book widespread in Islamic world, which contains the poetic narration in prose and verses of the birth of the Prophet. In Harar there developed a peculiar ceremony (here described as Mawlūd recital) for the reading of this sacred text, which includes the performance of zikri songs.

Cultural, historical and religious considerations can highlight the role that this practice has today. In recent history, the ritual traditions have been challenged by the restrictions imposed by the Christian Empire and later by the ruling Derg military regime. More recently the reformist action of Wahabiyya, especially influent during the 1980s and 1990s, accused the ritual activities at the shrine of being un-Islamic and promoted to establish more orthodox customs. Despite all the historical vicissitudes, Harari rituals are still practiced and, over the last ten years, has been revived in the daily life and especially in the major festivities collective celebrations, becoming, more than ever before, a major symbol of the cultural identity of the community.

Places, occasions and forms of the rituals

Harari rituals are performed in a variety of places, including the numerous local Muslim shrines, local worship places called Nabi gār (literally “House of the Prophet”), private houses and public spaces. It is possible to distinguish two main ritual forms: the zikri ritual and the Mawlūd recital, associated to several different occasions. In the Nabi gār and in the most important shrines, gatherings are held on a weekly base, mostly during the night between Thursday and Friday, at the beginning of the day devoted to prayer in Islam. Rituals are also organized whenever pilgrims pay a visit (ziyara) to a holy place. All the major festivities of the Islamic calendar are celebrated with zikri rituals or Mawlūd recitals. Furthermore, Mawlūd recitals are typically performed on Sunday morning, during the celebration of weddings. Finally, specific zikri rituals, called amuta karabu, are after a funeral.

The Nabi gār is a very distinctive devotional place. It is usually built beside a shrine and a Koranic school. Nabi gār have an important value as places of gatherings. Anyone can attend zikri rituals with no distinction of social status and limited distinctions based on gender. The most common and recognised form of zikri ritual takes place here on Friday eves. It is in the Nabi gār that Harari zikri songs were developed in their highest and original form, becoming an important instrument of devotion and, through their lyrics, a way to learn religion. The zikri repertoire accompanied by rhythms that are unique of this city probably developed inside the Nabi gār to fulfil teaching needs. Still today, in the Nabi gār it is possible to find some of the best zikri singers and karabu players.

The most important rituals in Harar are based on the reading of the Mawlūd, the sacred text about the birth of the Prophet. Even if there are slight variations according to groups, places and occasions, it is possible to describe the most common features of Mawlūd recitals in Harar. After selected passages from the Koran, including the first sura al-Fātihah, sura 36 Yā-Sīn, and sura 67 Tabāraka (or al-Mulk), the reading of the Mawlūd text is alternated with the performance of zikri songs; the ritual is concluded by a shared blessed meal. Mawlūd recital is an essential part of Harari wedding celebration and is typically organised during the morning of Sunday. The reading of the Koran usually starts between 08:00 and 09:00. The recital of the Mawlūd text begins between 09:00 and 10:00 and typically ends around noon, when, after a blessing for the bridegroom, the wedding lunch is served. During the singing of zikri , most of the assembly stands and some of the men dance in a circle, joined at some point by the bridegroom. The zikri performance is considered by many one of the most intense moments and, in order to make it successful, many families invite well-reputed zikri singers to the ceremony.

There is a peculiar form of zikri ritual, called amuta karabu , which is performed during the mourning time that follows a funeral. A shaykh is invited to the mourning house where all the women of the family’s neighbourhood association ( afocha ) are sitting together. He sings for them and with them a specific repertoire of hymns with texts pertaining to death and afterlife, together with some of the ordinary zikri. The ritual takes place in the morning hours, for two or three days.

Musical elements

The religious poems performed as zikri songs form a wide selection. Most of them come from a centuries-old tradition and their texts are written in manuscripts, often hand-copied by older religious men. The body of texts, in Arabic, Harari, and other local languages, despite being largely formulaic and referring to a widespread tradition of mystical literature, was developed significantly by local authors.

The responsorial structure of these songs is given by a solo voice, usually the conductor of the ritual, and by the assembly of participants. The texts themselves, chanted by the leading voice, are rather long and their performance may last up to almost one hour. The chanting is accompanied by two percussion instruments: karabu and kabal. Karabu is a kettledrum made from a bowl of wood that is covered at the top with cow or goat hide. It is played by hand or with two wooden sticks, usually wrapped at the top with a piece of fabric. Every important Muslim shrine in Harar keeps at least two drums for the ceremonies. Kabal are handheld wooden blocks that are clapped together by any of the participants in a zikri ritual.

The accompaniment to the singing is made according to three main rhythmic models.

The qasida karabu is based on a binary form, which consists of a continuous alternation of a high-pitched and a low-pitched beat. The qasida karabu is the most common beat and is often used for dancing.

Figure 1: Qasida karabu rhythm

Audio example

http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/music/zikri/audio/01QasidaKarabu.mp3

The quč quč is a binary form too. Here the high pitched beat can last double than the low pitched one, generating accents that usually follow those of the text. The percussive part stops when the solo voice is singing.

Figure 2: Quč quč rhythm

Audio example

http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/music/zikri/audio/02QucQuc.mp3

The harat chāla is a more complex model generated by combinations of four different patterns, this combination depending apparently on the organization of the text. The combination of these patterns is always repeated in the same way and it usually lasts as long as the whole refrain; during the solo singing, the percussive part stops.

Figure 3: Harat chala rhythm

Audio example

http://www.open.ac.uk/Arts/music/zikri/audio/03HaratChala.mp3

While the qasida karabu is played continuously and is suitable for dancing, the quč quč and the harat chāla , characterized by the interruption of the rhythmic part during the solo sung section, allow the participants to follow more carefully the meaning of the text sung by the main singer. The second and the third rhythmic models seem to be peculiar of the Harari performance tradition.

Systematic analysis of the zikri songs performed in Harar showed that the style of Harari chanting is usually strictly syllabic and does not present significant melodic ornamentation. Most of the melodies of the songs are based on varying ranges of a diatonic scale and they belong to three different modes, according to the pitch of their ending note.

Modes of Harari zikri melodies

Not available

Selected bibliography on zikri rituals

Banti, G. 2005 “Remarks about the orthography of the earliest c ajam ī texts in Harari” in S. M. Bernardini & N. Tornesello (eds.), Scritti in onore di Giovanni M. D’Erme, vol. I, Napoli, Università degli Studi di Napoli “L’Orientale”, pp. 75-102.

Bekele, Z. 1987 Music in the Horn… A preliminary analytical approach to the study of Ethiopian Music, Stockholm.

Braukamper, U. 1980 Islamicization and Muslim Shrines of the Harar Plateau, Addis Ababa, Addis Ababa University.

Braukamper, U. 1984 “Notes on the Islamicization and the Muslim shrines of the Harar Plateau” in Thomas Labahn (ed.), Proceedings of the Second International Congress of Somali Studies (University of Hamburg, August 1-6, 1983), vol. 2, Hamburg, pp. 145-174.

Cerulli E. 1936 Studi Etiopici. La lingua e la storia di Harar, Roma, Istituto per L’Oriente.

Cerulli E. 1971 L’Islam di ieri e di oggi, Pubblicazioni dell’Istituto per l’Oriente, vol. 64, Roma, Istituto per l’Oriente.

Foucher, E. 1988 Names of Muslimans venerated in Harar and its surroundings. A list, Zeitschrifder Deutschen Morgenlandiscen Gesellschaft, Stuttgart, pp. 263-282.

Foucher, E. 1994 “The cult of Muslim Saints in Harar: Religious Dimension” in Zewde B., Pankhurst R. & Beyene T. (eds.) Proceedings of the 11th International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, vol. II, Addis Ababa, Institute of Ethiopian Studies, pp. 71-83.

Gibb, C. 1996 In the city of Saints: Religion, Politics and Gender in Harar, Ethiopia, PhD Thesis, University of Oxford.

Gibb, C. 1998a “Sharing the Faith. Religion and Ethnicity in the city of Harar” in Horn of Africa, vol.16, pp. 144-162.

Gibb, C. 1998b “Constructing past and present in Harar. Ethiopia in a broader perspective” in Proceedings of the XII International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, vol. 2, pp. 378-390.

Gibb, C. 1999 “Baraka without borders: integrating communities in the city of Saints” in Journal of Religion in Africa, vol. 29, pp. 88-108.

Gori A., Bianchini R., Mohamud K.A. & Maimone F. 2003 Cultural Heritage of Harar. Mosques, Islamic Holy Graves and Traditional Houses. A comprehensive Map, CIRPS and Harari People National Regional State.

Tarsitani, S., 2007-2008 “ Mawlūd: celebrating the birth of the Prophet in Islamic religious festivals and wedding ceremonies in Harar, Ethiopia” in Annales d’Ethiopie Vol. XXIII, Addis Ababa, French Center of Ethiopian Studies (CFEE), pp. 153-176.

Tarsitani, S., 2007a “Kabal” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica Vol. 3, edited by Sigbert Uhlig, Wiesbaden, Harassowitz Verlag, p. 311.

Tarsitani, S., 2007b “Karabu” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica Vol. 3, edited by Sigbert Uhlig, Wiesbaden, Harassowitz Verlag, pp. 341-342.

Tarsitani, S., 2007c “Mawlid in Harar” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica Vol. 3, edited by Sigbert Uhlig, Wiesbaden, Harassowitz Verlag, pp. 879-880.

Tarsitani, S., 2006a “Musica religiosa islamica a Harar (Etiopia): i rituali di zikri ” (Islamic religious music in Harar, Ethiopia. Zikri rituals – article with audio and video examples on attached DVD), EM Rivista degli Archivi di Etnomusicologia, 2, Accademia Nazionale di Santa Cecilia, pp. 127-148.

Tarsitani, S., 2006b “Zikri Rituals in Harar: a Musical Analysis”, Proceedings of the XVth International Conference of Ethiopian Studies, Hamburg, pp. 478-484.

Tarsitani, S., 2005 “Dhikr in Harar” in Encyclopaedia Aethiopica Vol. 2, edited by Sigbert Uhlig, Wiesbaden, Harassowitz Verlag, pp. 158-159.

Trimingham, J.S. 1952 Islam in Ethiopia, London, Frank Cass & Co.

Wagner, E. 1973 “Eine Liste der Heiligen von Harar” in Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Band 123, Wiesbaden, Kommissionsverlag Franz Steiner GMBH, pp. 269-292.

Wagner, E. 1975 “Arabische Heiligenlieder aus Harar” in Zeitschrift der Deutschen Morgenländischen Gesellschaft, Leipzig – Wiesbaden – Stuttgart, pp. 28-65.

Waldron, S.R. 1975 Within the Wall and Beyond: Harari Ethnic identity and its future, History Society of Ethiopia, The History and culture of the peoples of Harar province (mimeograph).

Waldron, S.R. 1984 “Harari” in Weekes R. V. (ed.), Muslim Peoples: a world Ethnographic Survey vol. 1, London, Aldrich Press, pp. 313-319.

Zekaria, A. 2003 “Some remarks on the Shrines of Harar”, in Krupp & Hirsch (eds.), Saints, Hagiography and History in Africa, Frankfurt, Peter Lang, pp. 19-29.

You must be logged in to post a comment.