By Professor Dr. Philip Carl Salzman

Department of Anthropology

McGill University Montreal, Canada

About Author

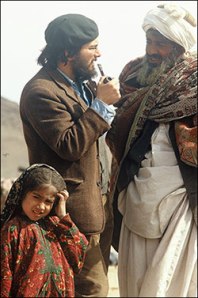

Dr Philip Carl Salzman during his research in Iran

Philip Carl Salzman is professor of anthropology at McGill University.He has carried out ethnographic research among nomadic and pastoral peoples in Baluchistan, Rajastan, and Sardinia. He is founder and past editor of the journal Nomadic Peoples and was awarded the 2001 Primio Pitrè- Salomone Marino from the International Center of Ethnohistory of Palermo for his book Black Tents of Baluchistan. His latest book is Culture and Conflict in the Middle East.

Profound changes

have occurred in the social and political life of the Baluch of Iran over the past century. Yet the fundamental principles underlying Baluchi social relations have remained unchanged.

The Baluch constitution

There are two constitutional political formations in Iranian Baluchistan. One is the tribe, which is the ultimate kin group to which loyalty is owed (Salzman 2000: Ch. 11). The other is the hakomate, a complex formation consisting of a small ruling elite, settled peasantry, and nomads, and which is integrated on bases other than loyalty (Salzman 1978a). I call the tribe and the hakomate “constitutional,” because each sets the basic rules within which its members operate. For example, the tribe defines and guarantees a territorial base and access to it, while the hakomate defines and enforces authority and subordination, and allocates resources accordingly. Every society faces the problem of security. Baluchi tribes and hakomates solve this problem quite differently. Tribes are based on kin solidarity, topak; Baluchi tribesmen look to their kinsmen to defend their interests. Baluchi tribal organization is based upon patrilineal descent: descent through the male line,

rend (Salzman 2000: Ch. 9). Patrilineal descent defines discrete, non-overlapping groups; earlier ancestors define larger, more

inclusive groups, while more recent ancestors define smaller, more exclusive groups. All members of a tribe trace their descent to the apical ancestor, after whom the tribe is commonly named, e.g. the Yarahmadzai are descendants of Yarahmad. At the same time, every sibling group of brothers and sisters are, by virtue of having a common father, a descent group.

Among the Yarahmadzai Baluch of the Sarhad region in northern Iranian Baluchistan, with whom I did my primary field research, certain levels of inclusiveness were marked. Groups based on five or six generations of descent, consisting of up to 150 souls, were vested with collective responsibility for defense and vengeance, and called, distinctively, brasrend, the group of brothers. The Yarahmadzai brasrend that I lived with and knew best, was the Dadolzai, the descendants of Dadol, although I also resided for a time with the chiefly lineage, the Yar Mahmudzai (Salzman 2000: Ch. 10). Uniting numerous brasrend was the minimal tribal section, which, in the case of the Dadolzai and Yar Mahmudzai, was the Nur Mahmudzai, and uniting various minimal tribal sections was the maximal tribal section, the Sohorabzai, which together with the Huseinzai and Rahmatzai were united as the Yarahmadzai tribe. While earlier and thus higher level ancestors were acknowledged, they did not define larger solidarity groups.

The brasrend was marked by the office of headman, mastair. (This is a specific application of a more general concept of seniority, mastair, which distinguishes between any two or more people, even brothers, on the basis of chronological seniority, leavened to a degree with capability and experience.) Minimal and maximal lineages were not represented by offices. The tribe among the Yarahmadzai, as among the Esmailzai, Gamshadzai, Rigi, and other tribes of Iranian Baluchistan, was marked by the office of chief, sardar (Salzman 2000: Ch. 11). The mastair and the sardar were leaders, not rulers. They were expected to consolidate, express, and act on public opinion. Coercion within the tribe was not part of their mandate. Their job was to secure consensus and peace internally, and to lead the defense against any external threat.

The underlying principle of adhesion and commitment in such tribal systems is relentlessly particularistic: unquestioned loyalty to my group vs. the other. It is not a matter of “my group, right or wrong”; “right or wrong” does not come into it. It is always a matter of absolute commitment to “my group” vs. the other.

Of course, in these tribal descent systems, which group is the referent, which group is “my group,” is contingent upon who is in conflict. If people of the Huseinzai are in conflict with some of the Soherabzai, then maximal tribal sections are the referents, and members of the Dadolzai and Yarmahmudzai act as Soherabzai. But if in another conflict, some Dadolzai are in conflict with some Yar Mahmudzai, then all Dadolzai are called upon to act as Dadolzai in opposition to the Yar Mahmudzai, their commonality as Nur Mahmudzai and Soherabzai and Yarahmadzai being not relevant to that conflict. For these Baluch, the Dadolzai unite against the Yar Mahmudzai; the Dadolzai and Yar Mahmudzai unite as Nur Mahmudzai against the Mir Golzai; the Nur Mahmudzai and Mir Golzai unite as the Soherabzai against the Huseinzai; and the Soherabzai and Huseinzai unite as the Yarahmadzai against the world.

This tribal system, called a “segmentary lineage system” by anthropologists, orders people by descent, and is thus a non-spatial form of socio-political organization. This is particularly helpful for pastoral nomads, who move around the landscape seeking pasture and water for their animals, distancing themselves from disease and threat (Salzman 1978b). Individual Baluch are inspired to conform to the rules of group identification and solidarity because they see their kin groups as their sole source of security on this earth. It is not primarily sentimentality, but a hard-headed assessment of interest that underlies

group solidarity, topak. Individuals act to advance the interests of their group(s) over the interests of others.

One consequence of this segmentary lineage system is a degree of peace through deterrence. The balanced opposition—of a small lineage vs. a collateral small lineage, of a tribal section vs. another tribal section, of a tribe vs. another tribe—discourages aggressive adventurism, because each group knows that another, more or less equivalent group, will form to oppose it and to seek vengeance (Salzman 2000: Ch. 10). Once conflict breaks out, neutral parties from structurally equidistant groups can be called upon to mediate and encourage peace. Here the sardar, representing the tribe as a whole, has a compelling responsibility to resolve conflicts and bring about peace.

But, as we should expect of human affairs, none of this— the balanced opposition, group solidarity, and conflict resolution—is mechanically perfect or always effectively enacted. The hakomate is, in contrast to the strong egalitarian and decentralized tendencies of the tribal system, hierarchical and centralized, and, in contrast to the largely voluntary basis of tribal action, is imposed and sanctioned by coercive force (Salzman 1968a).

Hakomates are based on the domination of oasis, agricultural populations by small elites, the ruler called hakom, his family hakomzat, in some cases who invaded and conquered. The ruling elite was supported by the tent dwelling, pastoral nomads, usually called baluch, in the control and exploitation of the oasis cultivators, called shahri. The baluch acted as enforcers, and received agricultural goods in payment. Hakomates, like agricultural oases, are more prevalent in the southern portion of Iranian Baluchistan, in Saravan and Makran, etc.

World turned upside down

The economies of Baluchi tribes and hakomates were largely subsistence oriented, with people producing for their own consumption, or for their ruler’s consumption. But in a place of rock and sand like Baluchistan, with dry years alternating with dryer, there were often shortfalls. The tribes compensated with predatory raiding, riding out on camel sorties to attack Persian villages in Kerman or caravans on the Persia-India route, carrying off agricultural stores, livestock, carpets, and other valuable goods, as well as captives to serve as slaves or be sold (Salzman 2000: Ch. 6). The hakomates, based in oases and relying more on irrigation crops, would have been able to ride out the drought years, perhaps squeezing the shahri a bit more.

But everything changed after Reza Shah’s military campaign in 1928-35 which brought Baluchistan under Persian control (Arfa

1964: Ch. 13). The tribes were “pacified” and forced to accept the suzerainty of the Shah. Consequently raiding was suppressed, and gradually the tribes were disarmed. Control was imposed over the hakomates, with various oasis forts knocked down by the Shah’s artillery. After the hiatus of World War II and the ascension of Mohammed Reza Shah to the throne, the process of integration of Baluchistan—now part of the Ostan-e Sistan o Baluchistan—into Iran continued. A provincial capital was built at Zahedan, in the far north of Baluchistan; district capitals were built in the main regions of Baluchistan. Persians— officials and ordinary civilians—began to trickle into Baluchistan, primarily but not exclusively into the towns. Eventually schools and clinics were built, some out in the countryside.

The position of the Baluch had changed radically. From being fighters and raiders, they had become the defeated, conquered by the Persians and their artillery and planes. From being politically independent, they had become dependent upon the will and whim of the Persian state and its agents and operatives. From operating their own, lineage-based control system, they found themselves subject to foreign and unknown laws and court procedures. From living off the fat of other people’s land, they found themselves forced back on their own meager economic resources. From living in their own language and culture, being culturally autonomous, they found themselves having to learn Persian and Persian culture. The world of the Iranian Baluch had been turned upside down.

Of course, tribal lineage organization did not disappear; it continued to operate for local matters, within some constraints imposed by state supervision. For example, there was a low grade violent conflict between two tribal maximal sections of the Yarahmadzai during 1972-76, flaring up from time to time, quiescent from time to time, but demonstrating the continued vitality of lineage solidarity and opposition. The sardar by necessity became an intermediary between the state and the tribe, mediating between the two while trying to satisfy both. For the first time able to draw on the rich resources of the state, he was able, in a small way, to become a patron to tribesmen, and managed to do well for himself while doing good for the tribe. He could also call on the state, in a limited way, to back him in his chiefly duties, such as resolving conflicts, e.g. that between the tribal sections (mentioned above).

Islamic intensification

During the 1960s and 1970s there was an increased attention among the Yarahmadzai Baluch to religion (Salzman 2000: Ch. 12). For the first time ever, Yarahmadzai, in this case senior members of the chiefly family, went on the haj, to be follow shortly by elders from various lineages. The sardar sponsored and supported a learned religious leader, a maulawi, as part of his retinue, building a small madrasse and residence at his headquarters, and recruited students and an assistant teacher for them. Friday prayer for all, led by the maulawi, was held (outdoors) at the sardar’s headquarters. Large prayer and instruction meetings, often led by mullas from outside the tribe, were called in the tribal territory, commonly out in open country. Ordinary tribesmen returned from these meetings inspired, and passed on instruction to their wives and children. Young men, of increasing number, were choosing to go to Pakistan to study in the religious schools there, taking on the mantle of the talib. In herding camps, playing the radio, listening to music, and other unseemly, un- Islamic behaviors, were looked on with increasing severity. It seems apparent that there was more and more place in the lives of the Baluch for their religion. I think it would be fair to call the general process “Islamic intensification.” No doubt there are many factors underlying this religious intensification among the Baluch. One would be sheer opportunity, made possible by improved communication and transportation, and by greater participation in the money economy: it became easier to hear about religion on the radio, easier to go to religious events and to faraway religious schools, easier to bring in and compensate religious authorities. But opportunity is not motivation, and I believe that two other factors have played a large role in Baluchi religious intensification.

The first is the loss of many bases of achievement and identity. The Baluch had been intrepid warriors and relentless raiders, but they were no more, having been defeated and conquered by the Persians. The Baluch had been proud of extracting a living from their barren and intractable land, but the Persian showed themselves to be incomparably richer and more economically successful.

The Baluch had been masters in their own land, governing themselves as they pleased, but they had become subjects of the all-powerful Iranian state, and reduced to politely requesting permission to come and go, and to arrange this or that local affair. Baluchi language, dress, knowledge, and customs had been the standard of correct behavior, but was now marginal and rustic, replaced by Farsi, and by Persian dress, knowledge, and customs. The Baluch had become “backward” in their own land. With the loss of the military, economic, political, and cultural bases of achievement and identity, the Baluch faced an increasingly obvious vacuum in their lives. They filled this vacuity by turning to religion. Islamic intensification was for the Baluch the expansion of religious concerns, activities, and satisfactions to replace those lost to the Persians. A newly emphasized identity as the “observant Muslim” and “the good man,” and for some, “the talib” and “learned” took the place of the intrepid warrior and tenacious husbander.

The Persian conquest of Baluchistan had raised a great question for the Baluch: who were they now? Islam supplied the answers. Second, Islam could supply the answer for the Baluch who had been undermined by the Persians, because Baluchi Sunni Islam was distinct from Persian Shi’a Islam. However superior the Persians had proven themselves in the battlefield, in the marketplace, and in the administrative offices and courts, Persian religion could always be challenged as incorrect by the Baluch, who saw themselves as following the true path of God. Some Baluch at least were ready to say that the Persians were hardly Muslims. There was no Baluchi doubt that in religion they were superior to the Persians. And the more religious they were, the more superior they were. In this light, Islamic intensification among the Baluch appears understandable.

The beauty of religion is that, while military prowess is tested on the battlefield, economic effectiveness in the marketplace, and political power in offices and courts, religion is never tested on this debased earth, but only in the glorious hereafter (from which reports are scarce). So anyone, however disadvantaged in this life, can claim that they, indeed they alone, follow God’s truth, that others are benighted and ignorant, if not outright evil, and there can be no decisive contrary reply to such an assertion.

Segmentary opposition all the same

Is the turn to religion among the Baluch a revolution in Baluchi social organization? Is the underlying principle of Baluchi segmentary organization—unquestioned loyalty to my group vs. the other—violated and overturned?

Is not the Islamic community, umma, inclusive and unified? For the Baluch, at least, their Sunni religion is—in good segmentary spirit—opposed to that of the Shi’a Persians. Indeed, I would suggest that the opposition between the Baluch and Persians itself has fueled the religious intensification among the Baluch. Thus segmentary opposition is replicated at the ethnic group level—Baluch vs. Persians—and in religion—Baluchi Sunnism vs. Persian Shi’ism.

My construing of Islam in a framework of segmentary opposition might seem outlandish or reductionistic. And yet nothing is more basic to Islam than its opposition to the superseded religions of Judiasm and Christianity, and to the paganisms of Zoroastrianism, Hinduism, Bahaiism, etc., all characterized as false belief. Muslims are opposed to infidels, kafir. This is more than a notional opposition. Muslims are acting on behalf of God, and must convert, subordinate, or kill kafir. This was the program of the great Islamic Empire, which spread across much of the known world. The Ottoman Empire followed in the same spirit. Contemporary Islamist movements continue the tradition. This segmentary opposition and underlying particularism might be surprising, were it not well known that Islam was born, nurtured, and carried forth almost exclusively by Bedouin, whose tribal system, like the Baluchi tribal system, is entirely based on segmentary opposition and exclusive, particularist loyalty.

I would venture to say that the step from Sunnism vs. Shi’ism to Islam vs. the infidel would be easy for the Baluch of Iran to take. That they have been studying in Pakistani madrasse, where such emphases are common, would only facilitate the shift to this higher-level oppositional particularism. •• This paper was presented at the conference on Tribal Politics and Militancy in he Tri-Border Region, held in Monterey, California, September 21-22, 2006. I carried out ethnographic field research in Iranian Baluchistan in 1967-68, 1972-73, and 1976, for a total of 27 months. The main report of my findings is Salzman 2000.

References cited

Arfa, Hassan

1964 Under Five Shahs. London: John Murray.

Salzman, Philip Carl

1978a “The Proto-State in Iranian Baluchistan,”

in Origins of the State, Ronald

Cohen and Elman Service, editors.

Philadelphia: ISHI.

1978b “Does Complementary Opposition Exist?”

in American Anthropologist

80(1):53-70.

2000 Black Tents of Baluchistan. Washington,

DC: Smithsonian Institution Press.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………

COURTESY By:

Middle East Papers

Middle East Strategy at Harvard University

June 20, 2008 :: Number Two

You must be logged in to post a comment.